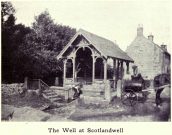

Holy Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 6983 4138

Archaeology & History

Shown on the 1864 OS map of the area as a ‘Well’ just at the front of St Bride’s Chapel—now a very pleasant old cottage—peasants and pilgrims would stop for both refreshment and ritual here as they walked down High Kype Road. Although the chapel was described in church records of January 1542 as being on the lands of Little Kype, close to the settlement of St Bride, there seems to be very little known about the history or traditions of the well. If anyone has further information on this site, please let us know.

Folklore

Bride or Brigit has her origins in early British myth and legend, primarily from Scotland and Ireland. Her saint’s day is February 1, or the heathen Imbolc (also known as Candlemas). Although in christian lore St. Bride was born around 450 AD in Ireland and her father a Prince of Ulster, legend tells that her step-father (more probably a teacher) was a druid and her ‘saintly’ abilities as they were later described are simply attributes from this shamanic pantheon. Legends—christian and otherwise—describe Her as the friend of animals; possessor of a magickal cloak; a magickian and a healer; and whose ‘spirit’ or genius loci became attached to ‘sacred sites’ in the natural world, not the christian renunciation of it. St Bride was one of the primal faces of the great prima Mater known as the Cailleach: the greater Gaelic deity of Earth’s natural cycles, whose changing seasons would also alter Her names, faces and clothes, as Her body moved annually through the rhythms of the year. Bride was (and is) ostensibly an ecological deity, with humans intrinsically a part of such a model, not a part from it, in contrast to the flawed judaeo-christian theology.

References:

- Paul, J.B. & Thomson, J.M., Registrum Magni Sigilli Regum Scotorum: The Register of the Great Seal of Scotland AD 1513 – 1546, HMGRH: Edinburgh 1883.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian