Healing Well: OS Grid Reference – SE 1159 4343

Also Known as:

- Redmire Spa

- Redmond’s Spa

- Richmond’s Spa

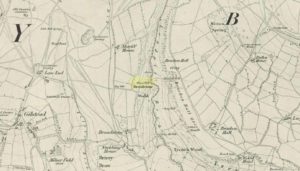

From East Morton village, take the moorland road, east, and up the steep hill. Where the road just about levels out there’s a right turn, plus (more importantly!) a trackway on your left which leads onto the moor. Walk up this track for ⅔-mile until you get to the point where the moorland footpath splits, with one bending downhill to an old building, whilst the other smaller footpath continues on the flat to the north. Go up here for 400 yards then walk off-path, right, for about about 150 yards. But beware – it’s boggy as fuck!

Archaeology & History

On this featureless southern-side of Rombalds Moor, all but lost and hidden in the scraggle of rashies, a very boggy spring emerges somewhere hereabouts. I say hereabouts, as the ground beneath you (if you can call it that!) is but a shallow swamp and its actual source is almost impossible to locate. If you want to find the exact spot yourself, be prepared to put up with that familiar stench of bog-water that assaults our senses when we walk through this sort of terrain. Few are those who do, I have found… But somewhere here, amidst this bog—and still shown on the OS-maps—is the opening of what is alternatively called Redman’s or Richmond’s Spa. We don’t know exactly when it acquired its status as a spa-well, but the 18th century Halifax doctor, Thomas Garnett—who wrote the early work on the Horley Green Spa—appears to be the first person to describe it. Garnett (1790) said how the place:

“was first mentioned to me by Mr W. Maud, surgeon, in Bradford, who went with me to see it. It is situated on Romalds-moor, about two or three miles from Bingley, and goes by the name of Redmire-spaw. The access to it is by no means good; the ground about it being very spongy and soft. On the bottom and sides of the channel is deposited an ochrey matter, of a very fine, bright, yellow colour; and which I believe is used, by the country people in the neighbourhood, to paint their houses. It sparkles when poured into a glass and has a taste very like the Tewit-well at High-Harrogate; which water it very much resembles in all its properties, and seems to be about the same strength… This water seems to hold a quantity of iron dissolved by means of fixed air. Its taste is very pleasant; it is said to act very powerfully as a diuretic, when drank in considerable quantity, and may prove a useful remedy, in cases where good effects may be expected from chalybeates in very small doses; the fixed air, and even the pure water itself may be useful in some cases. It is, however, necessary to drink it at the well, for it seems to lose its iron and fixed air very soon.”

I’ve drank this water, and believe me!—it doesn’t quite taste as pleasant as Mr Garnett espouses! Its alright I s’ppose—but drinking water from a bog isn’t necessarily a good idea. That aside, I find it intriguing to hear so much lore about such a little-known spring; and it is obvious that the reputation Garnett describes about this spa came almost entirely from the local people, who would have been visiting this site for countless centuries and who would know well its repute. Below the source of the well the land is known as Spa Flat, and slightly further away Spa Foot, where annual gatherings were once held at certain times of the year to celebrate the flowing of the waters. Such social annual gatherings suggests that the waters here were known about before it acquired its status as a spa—which would make sense. The remoteness of this water source to attract wealthy visitors (a prime function of Spa Wells) wouldn’t succeed and even when Garnett visited the place, he said how he had to travel a long distance to get here.

The origin of its name was pondered by the great Harry Speight (1898) who wondered if it derived from the ancient and knightly Redman family of Harewood, whose lands reached over here. But he was unsure and it was merely a thought. As an iron-bearing spring (a chalybeate) you’d think it might derive from being simply a red mire or bog (much like the Red Mire Well at Hebden Bridge), but its variant titles of apparent surnames casts doubt on this simple solution.

No one visits the place anymore. Of the countless times I’ve wandered the moors, rare have been the times when I’ve seen folk anywhere near this old spring. It is still coloured with the same virtues that Garnett described in the 18th century: the yellowish deposits, the boggy ground, much of which reaches to the truly dodgy Yellow Bog a short distance north and which should be completed avoided by ramblers after heavy rains (try it if y’ don’t believe me—but you’ve been warned!).

References:

- Garnett, Thomas, Experiments and Observations on the Horley-Green Spaw, near Halifax, George Nicholson: Bradford 1790.

- Short, Thomas, The Natural, Experimental and Medicinal History of the Mineral Waters of Derbyshire, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, privately printed: London 1724.

- Speight, Harry, Chronicles and Stories of Old Bingley, Elliott Stock: London 1898.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian