Stone Circle: OS Grid Reference – SE 12605 46130

There are many routes to get here, but this is the one I usually take. From Cow & Calf Rocks, walk up the steep hillside onto the first moorland plain, taking the path right, diagonally, across to the NW as if you’re heading to the Map Stone. From here, looking down at the stream valley below, follow the valley edge up, past the settlement, and then veer down to Backstone Beck and up on the other side till you meet with a footpath and also up in the heather ahead of you, notice the jumbled walling less than 100 yards away. That’s where you need to be!

Archaeology & History

A singular short sentence in Robert Collyer and J.H. Turner’s Ilkley, Ancient and Modern (1885) started it all off, where they told:

“There was still a rude circle of rocks on the reach beyond White Wells fifty years ago, tumbled into such confusion that you had to look once, and again, before you saw what lay under your eyes.”

…..And thankfully this is still what we see today – and in just the area they mentioned.

I’m intrigued to find there’s so much said about this site on the Net and feel I should put my recent feelings about the place to print at last (and after being badgered to gerrit done by James Elkington!). The information about its make-up and the mess it’s in, hasn’t changed since we rediscovered the place on June 3, 1989. Here, amidst the tall grasses and reeds of Juncus effusus and J. conglomeratus, our jumble of megaliths hides within a breakdown of fallen walls, that are thought to have been part of some sheep-fold or a similar animal enclosure (mebbe for the annual sheep-shagging contests that are held, quietly, on these moors each year!).

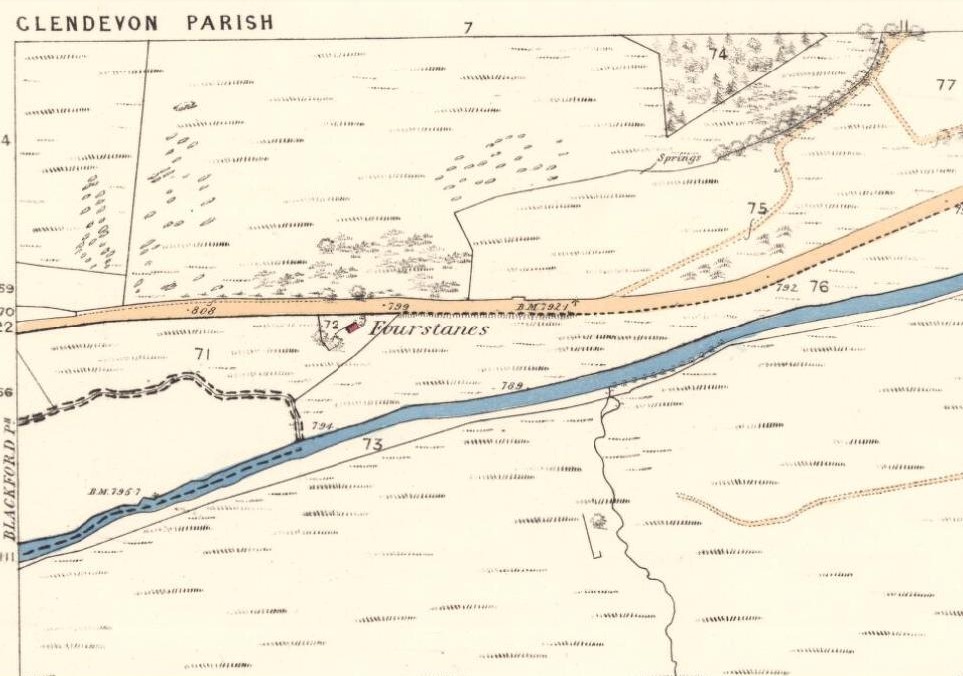

The name ‘backstone’ itself come from the adjacent beck (slowly depleting as the years pulse by) and is mentioned in the 18th century parish registers. A.H. Smith (1961) informs us that it was the “stream where bakestones were got”, and this was probably a tradition going way way back. The baking stones from the beck may even have been used by the people living in the prehistoric settlements close to the circle.

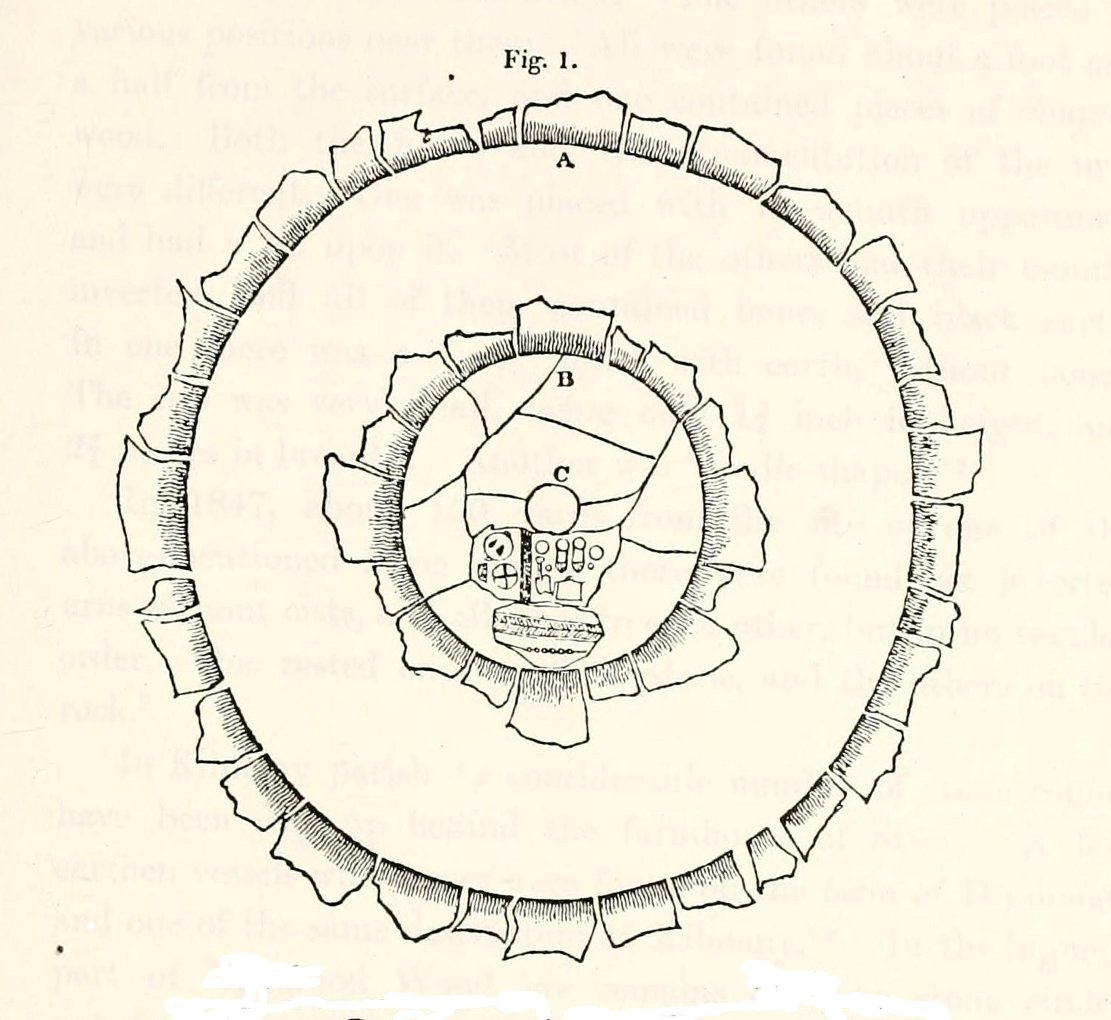

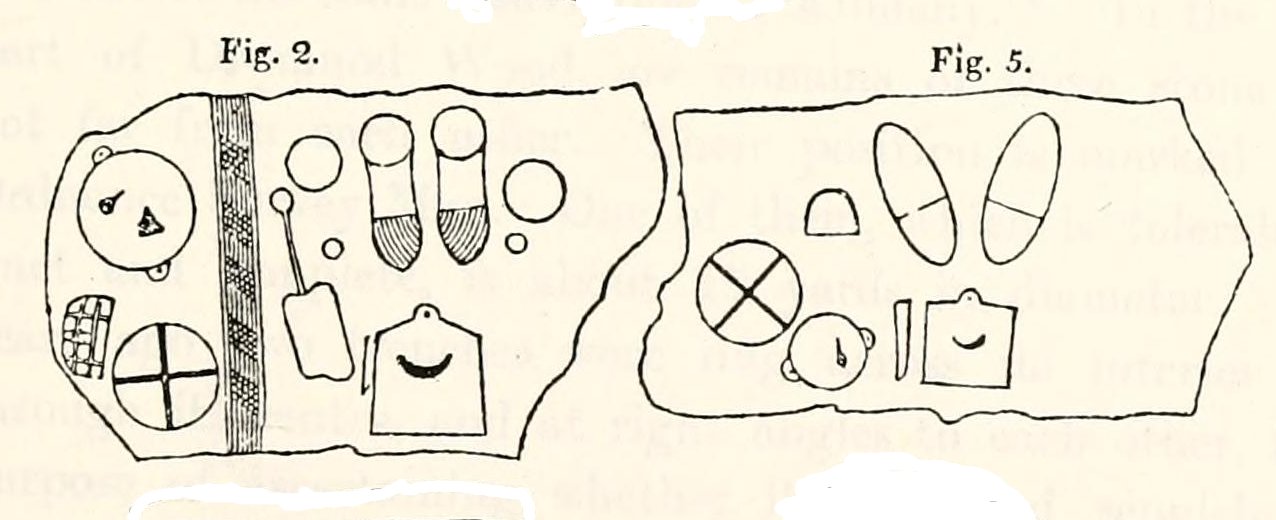

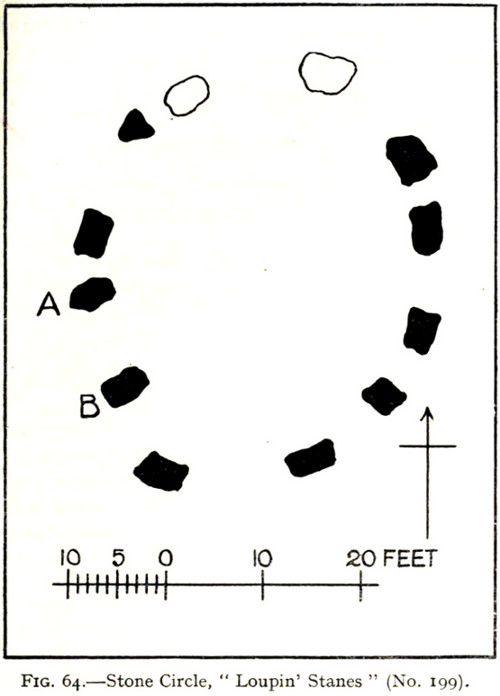

In what looks today like a messy double-ring of stones, it’s likely there was originally just a single ring which has, subsequently, been knocked down and re-used for some form of sheep-fondling sessions—be it agricultural or otherwise! But for the record at least: we have small inner ‘ring’ of four upright stones, re-worked in more recent centuries, between two-and-a-half to three-and-a-half feet tall. Another stone is recumbent. The outer ring is more conspicuous. It consists of at least eight standing stones–seven of which are upright–between three and five feet tall, some of which have been re-worked in more recent times. There are several other stones either recumbent or partly covered by vegetation. The tallest of the stones is 4’11” tall. The outer circle has had at least one of the stones uprooted and used at the base of the dry-stone walling intruding the southwest side of the circle. What appears to be at least two original standing stones are embedded into earthworks on the other side of this wall, one of which was located through dowsing!

The best section of the ring can be seen on its eastern side, where an arc of upright stones between three and four feet high are still clearly in evidence, just inside a raised embankment like that found surrounding the Twelve Apostles stone circle less than a mile away.

A short while after finding the site, we contacted the Ilkley Head of Archaeology Studies, Gavin Edwards, about the circle and he subsequently included the site on one of the tourist-guides to the moors.

Alignments through this circle seem apparent in situ; and although such alignments are intriguing (to me anyhow), it’s the geometric relationship Backstone has with other circles on these moors that is rather notable. It’s position in the landscape plays an essential part in an isosceles triangle formation, 1180 yards [1.08km] from the Twelve Apostles stone circle which, as the centre point, is another 1180 yards from the Roms Law Circle. Odd….

Immediately visible from our ruinous circle across the small valley to the slopes of Green Crag, the Ilkley Archaeology Group spent more than fifteen years excavating the remains of what was initially thought of as a Bronze Age village, but their work here has proved startling, pushing the date of human occupation here into the mesolithic period! Local archaeologist Gavin Edwards opined that the Backstone circle would have been the religious site for the people who lived here. I have to concur. There are also more neolithic and Bronze Age walling, indicative of extended settlements and enclosures, less than 200 yards north of the Backstone Circle, structurally consistent with the remains across the valley at the excavated Green Crag Slack settlement.

Ten yards east of the circle is a small well which only runs following exceptional rainfall. This was probably of some ritual importance to the people who practiced rites here. Geological fault lines run not far away on three sides of the ring and an underground stream is present, quite close to the surface (as indicated by the presence of Juncus conglomeratus and J.effisus), encouraging the preponderance of regular electromagnetic variations: these in particular are likely to have some causative influence on the paranormal events described below….

Fortean History

Since rediscovering this site, a number of bizarre psychophysical anomalies have been experienced and described by more and more people — some of whom were previously very sceptical of such things. Both day and night, no doubt when Moon and water speak their subtle electromagnetic accord, a gathering corpus of all-too-familiar events keep speaking of a most disturbing resident spirit…

We begin on Wednesday, July 12, 1989, sometime around midnight, when an acquaintance and I were spending a few days here to record any possible electromagnetic anomalies at this disturbed ring of stones. We weren’t to be disappointed, as something very untoward raised its peculiar head.

As I sat barely ten yards beyond the tumbled group of stones there suddenly appeared, from nowhere, a host of figures—a dozen at most—walking ever so slowly around the old site. I could discern no physical features other than their height and humanoid shape. It was just too dark to see any details about them—they were, effectively, silhouettes. My acquaintance was terrified—although it was perhaps a minute or so before he even glanced at what I was pointing and exclaiming at, somewhat manically, stuttering and shaking my head in an attempt to make the things disappear back to my unconscious where they surely originated. Didn’t work though!

These were no psychic projections. I literally shook my head, closed my eyes and knocked my head against the walling; looked away, shook my head again, shouting at myself and looked back at the figures in front of us. It still didn’t do a damn thing! By now my friend was staring, aghast and scared shitless if the expression on his face was anything to go by.

“Wot a’ y’ seeing? Wot can y’ see?” I asked.

He murmured and mumbled something about some people he could see, walking round and round the old remains.

He was seeing exactly the same as what I could see. As the minutes passed by, this group of people, who were winding in and out of each and every stone and walking through the intrusive walling as it was not there, slowly but surely, ever so gradually, increased in speed. This was very slow and patient and went on for at least fifteen minutes — by which times they were barely visible as individual figures anymore. All we could see by now was a visual blur and a remarkable vortex that was created in the wake of their ‘dance’.

This spinning vortex of silhouettes seemed to get faster and faster until appearing to reach a sort of critical speed/energy state — and as this “critical state” occurred, what was by now a rapid spinning, energetic blur simply vanished right before our eyes! It was as if someone, somewhere, had flicked a switch and they disappeared. Yet, at the very same moment the blurred vortex vanished, several dead straight lines of orange-red appeared in their place. These were as baffling as the dance we had just watched: very thin, wavering lines of what I can only describe as subtle light, bounced off several of the standing stones. These lines—perhaps four of them—did not originate from the circle but appeared to come from further afield. One in particular seemed to come from the direction of the great boulder known as the Idol Rock, 700 yards [650m] east and continued past our field of vision in the direction of the Swastika Stone.

To be honest these “lines of energy” perturbed me more than the spinning figures which had just disappeared. Not only were these lines two-dimensional [a real screw-up that one!], I was at a loss to explain what these lines really were. The first thought was, of course, leys – but my idea of leys did not, and still does not accord with what I was seeing. Eventually the lines faded back to wherever they came, leaving both of us wondering what the hell we had just experienced.

Several minutes after talking over what had just happened, I stood up and walked into the circle. At this point, please remember it was July 12 and the night was so warm that neither of us had taken sleeping bags or a tent onto the high moors with us. As I got to the circle and took my first step inside, a tremendous shiver hit right through my body, almost like I was walking into a freezer. But I moved another step forward, unperturbed if truth be had by the probable chill wind that made me shiver. As I did so, the chill became more manifest and intense. As I took my third step forward the cold became biting and I collapsed onto my knees. [This is not like me, honest. Give me camping in the Scottish mountains in mid-February with average temperatures of -6 degrees and that’s my idea of a good night out!]

Shivering like hell, I stumbled upright and back onto my feet and virtually ran out of the circle. That, more than anything else that night, truly perturbed me.

The following morning another volunteer joined us. We told him about the events of the previous night and he thought whatever he thought; but he’d brought two thermometers with him and set them on two of the rocks: one of them about 25 yards outside the circle, the other on a stone in the circle. The two of them had the same reading: 73° F. We left them without checking for a good hour or so and then began to take readings. What transpired was bizarre to say the least: the one outside the circle was 62° F, the one in the circle was 72° F. A further reading fifteen minutes later, close to sunset, showed the temperature variations had come a little closer: the inner reading was 70° F, and outer reading still 62° F. Readings were then taken every fifteen minutes and the respective readings closed in on each other until both were the same, exactly when the sun was touching the horizon to set, at 9.05pm. But this was not the end of the anomaly. While the temperature outside the circle dropped naturally with nightfall, finally resting at 57-58° F, the inner circle reading continued falling at nearly twice the background rate! Our final reading after 11pm showed a deviation of nearly 7 degrees between the respective thermometers!

If these elements seem in anyway somewhat unbelievable, what occurred next bends the parameters of reality still further!

No further anomalous Fortean events happened at the circle that night—for us at least. However, a friend in Leeds—the internationally renowned ritual magician and author, Phil Hine—was at home with some friends, chatting.

“On the night in question,” he came to write sometime later, “I was talking to another magickian. He returned from the toilet and informed me that there was an “entity” lurking in the stairwell… This was unusual, but not sufficiently unusual to cause undue concern, and so, picking up my thunderbolt, I went out to see what was what. In the stairwell we both agreed on seeing a black amorphous shape. Since my friend had first noticed this, I asked him if he would be prepared to “open his mind” to it, so that I could question it, using him as an interface [which was one of his particular talents] and a fairly accepted procedure for questioning strange entities. “The entity declared,” I have come from the ancient hills.” It also stated that it had been “awakened” only recently due to activity around a sacred site. It said that it had come to give me “power” with which I could do something, but was reticent about the exact nature of this. When I asked what it would do if I rejected this, it said that it would return “screaming to the hills.” When I asked it to identify itself it gave the name Azathoth—which could well have sprung from the mind of my friend, although he had no particular knowledge of the Cthulu mythos entities.”

Phil continued:

“At the time I found it difficult to credit that such a powerful entity would be hanging politely about in the stairwell waiting to be noticed. Being unable to obtain a direct answer to my questions, I told it to go forth, which it apparently did. I later had to perform an intense banishing ritual on my friend who was suffering from symptoms such as feeling cold, a tight pressure on the chest, personality displacement, and motor spasms… Unbeknownst to me at the time, two friends of mine who were members of the West Yorkshire Earth Mysteries Group had experienced a strange encounter at the then newly-uncovered Backstone Circle on Ilkley Moor… It seems strange, on reflection, that the appearance of the entity claiming to originate from a newly disturbed site seems to relate to their experience.” [Hine 1994, 1997]

Other bizarre experiences at the circle itself have been reported by growing numbers of people—a lot of them quite unpleasant. One lady, Katy from Calderdale, whose interest in megaliths rarely stretched into the obscurities of their folklore or weird tales, will “probably never go there again. It terrified me. I don’t know why, there was nothing to be scared of, but the place just felt awful.”

There have been at least a dozen people who have related the same words to me—and I can empathise. On February 14, 1990, Mick N. and I went to the site for the night with intent to do a bit of sympathetic ritual magick. The night was cold and a slight fall of snow glittered across the moors as far as we could see, invoking quite healthy feelings about the forthcoming rite. But as we turned off the path and approached the stones, it was as if we had walked through an invisible gate or door just yards before the circle itself, screaming quite powerfully with gnarled teeth that we were not wanted there that night! It was overwhelming! We both acted accordingly and spent the night elsewhere, cold and querying over its genius loci. The potency of Azathoth seemed inherent in its silent voice.

This particular feeling, almost of malevolance, has been described by many people at Backstone. It occurs both day and night and is akin to what Prof Thomas Lethbridge (1961) described as ‘ghouls’: place-memories so to speak, or spirits of place. Most of the time there is no such feeling, of course. But when conditions are right, these potent subjective consumations can be quite overwhelming at some spots. They are reported worldwide in the aboriginal traditions of all races and are felt, obviously, even today by explorers, mountaineers and visitors to ancient haunted places like the Backstone Circle.

Strange lights have also been seen over and around here by a number of witnesses. On one occasion a ritual invocation of its spirit-nature brought forth a number of glowing red spheres of light. These were about the size of footballs, appearing for a minute or two, floating in front and around us, then vanishing—only to reappear yards away around the edges of the damaged ring of stones. These were very obviously living things and were examining us with equal bewilderment. Other light-phenomena that people have seen here and on this moor appear to relate to the phases of the Moon.

Although the site is quite ruinous, it is a worthwhile place to visit – just respect, and beware the Old Hag who sometimes comes forth from time to time….

…to be continued…

References:

- Bennett, Paul., “The Backstone Circle,” Earth 15, 1990.

- Bennett, Paul, “Archaeological and Geometrical Applications of the Lost Stone Circle of Ilkley Moor,” Earth 15, 1990.

- Bennett, Paul, Circles, Standing Stones and Legendary Rocks of West Yorkshire, Heart of Albion Press: Wymeswold 1994.

- Bennett, Paul, “The Strange Case of Backstone Circle,” Right Times 1, 1998.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Bennett, Paul, The Twelve Apostles Stone Circle, TNA Publications 2017.

- Collyer, Robert & Turner, J. Horsfall, Ilkley: Ancient and Modern, William Walker: Otley 1885.

- Devereux, Paul, Places of Power, Blandford: London 1990.

- Gyrus T., “An Interview with Phil Hine,” Towards 2012 volume 4, 1998.

- Hine, Phil, “The Physics of Evocation,” Chaos International 1990.

- Roberts, Andy, Ghosts and Legends of Yorkshire, Jarrold: Norwich 1997.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 4, Cambridge University Press 1961.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks to Richard Stroud for his photo of Backstone at winter time; to James Elkington for saying, “Come on Paul – get yer finger out!” + his photos too…

Links:

- Backstone Circle on The Megalithic Portal

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian