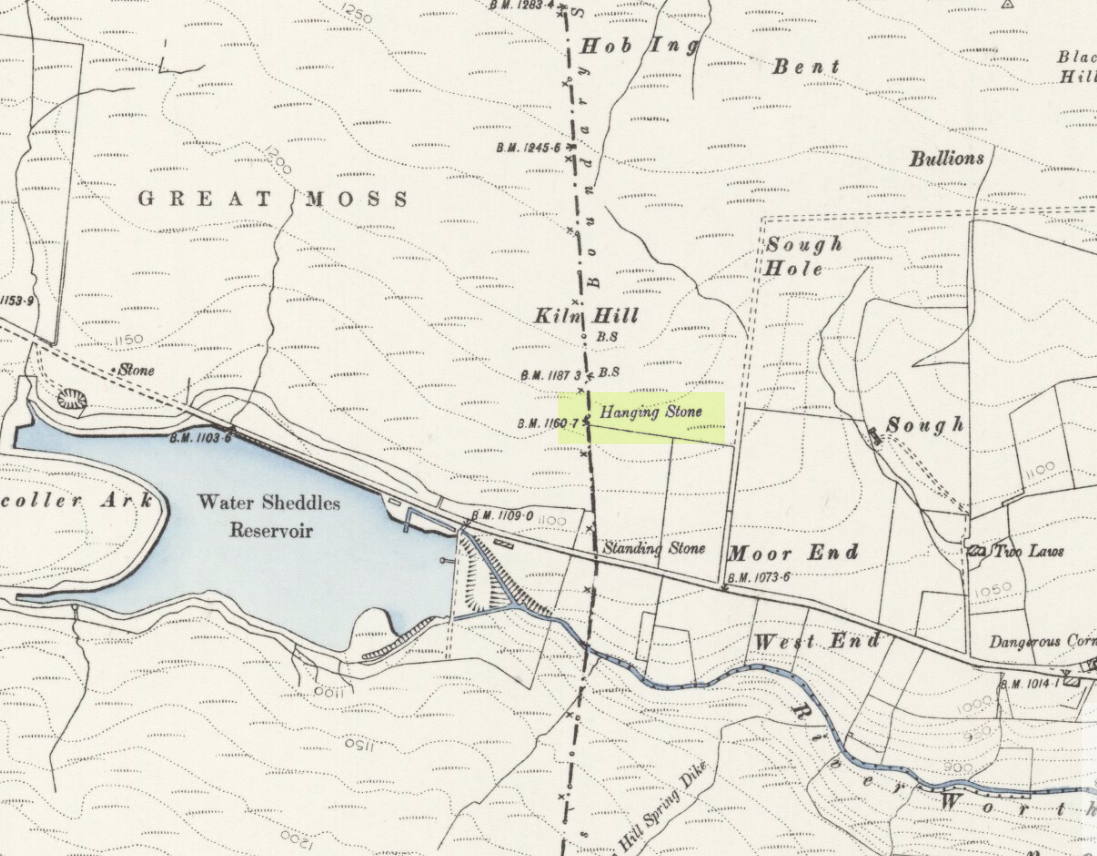

Standing Stone (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 15940 34211

Also known as:

- Ash Stone

- Pin Stone

Archaeology & History

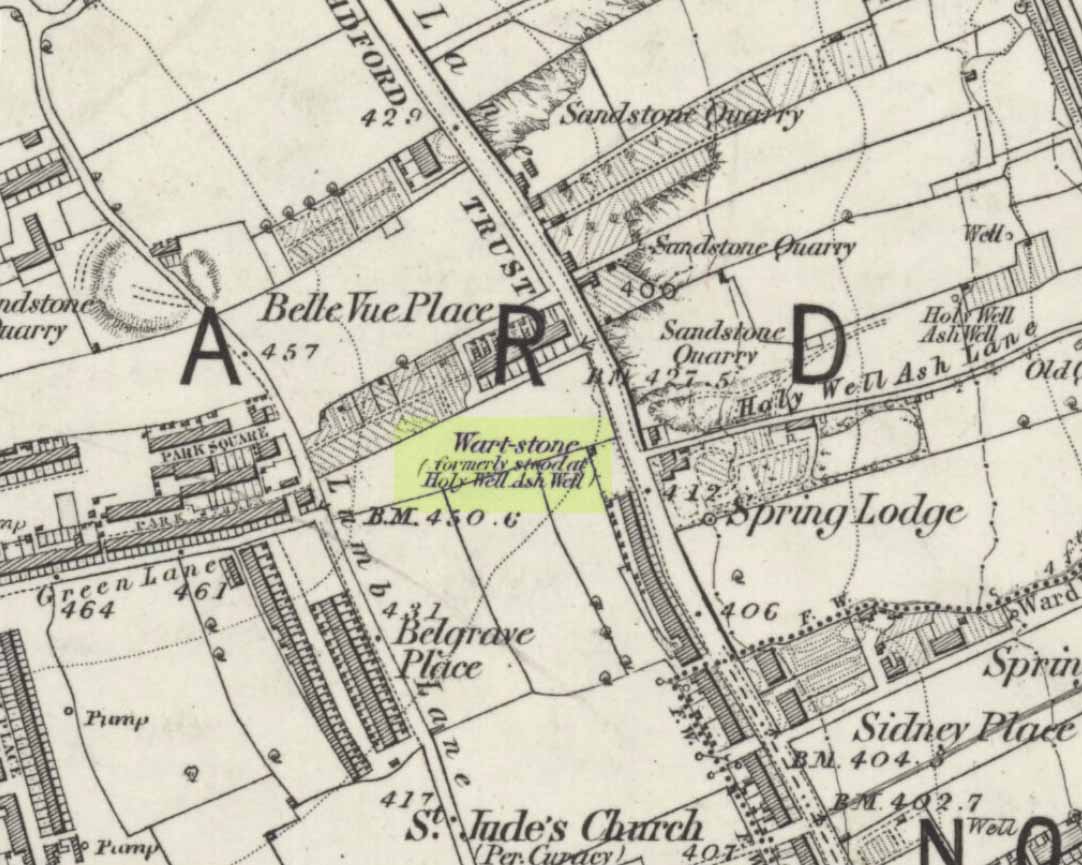

At Bradford City’s football ground there used to be the holy well known as the Holy Ash Well, adjacent to which was this old stone (as shown on the 1852 OS map). For some reason it was uprooted and moved further up the hill around the end of the 19th century and was resurrected beside the old Belle Vue Hotel on Manningham Lane. From thereon however, I’ve not been able to trace what happened to it, and presume it’s been destroyed. It was known by local people to have had a ritual relationship with the adjacent healing well, to which people were said to visit from far and wide.

It seems to have been described first by Abraham Holroyd (1873), who told us that:

“In Manningham Lane there is a fine well, in old deeds called Hellywell, i.e., holy well, in a field now called Halliwell Ash, now a stone quarry… Near this is the ancient Pin Stone.”

The Bradford historian William Preston also made mention of the stone in one of his early surveys, where he told how local people also knew the stone as the Ash Stone, due to its proximity and ritual relationship to a great old tree.

Folklore

Also known as the Wart Stone, thanks to its ability to cure them and other skin afflictions. Intriguingly, the building which now stands on the site is said to be haunted.

As my old school-mate, Dave Pendleton (1997), said of the place and its associated well:

“Prior to 1886 the only feature of any real note in the Valley Parade environs was a holy well that emerged near the corner of the football grounds Midland Road and Bradford End stands; hence the road Holywell Ash Lane. Today the site of the well is covered by the football pitch.

Only the road name survives as a reminder of what was apparently one of the district’s foremost attractions. On Sundays and holidays people would gather to take the waters and leave pins, coins, rags and food as offerings to the spirit that resided in the waters.

Accounts suggest that the well was covered and had a great ash tree standing over it (hence ‘holy ash’). There was also a standing stone called the wart stone of unknown antiquity. The stone had a carved depression that collected water. It was believed that the water was a miraculous cure for warts. Indeed, as early as 1638 the Holy Well had been credited with healing powers.

The well suffered a decline in popularity during the late nineteenth century and its keepers resorted to importing sulphur water from Harrogate, which they sold for a half penny per cup. The well disappeared under the Valley Parade pitch during the summer of 1886 and the wart stone was moved to the top of Holywell Ash Lane – which then ran straight up to Manningham Lane. The stone was still there as late as 1911 but thereafter it seems to have disappeared into the mists of time.”

Unfortunately we have no old photos or drawings of this lost standing stone – though I imagine that some local, somewhere must be able to help us out with this one. Surely there’s summat hiding away…

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Holroyd, Abraham, Collecteana Bradfordiana, Saltaire 1873.

- Pendleton, David & Dewhirst, John, Along the Midland Road, Bradford City AFC 1997.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian