Standing Stones (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – HY 497 509

Archaeology & History

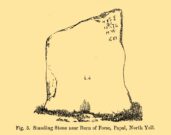

These long lost standing stones most probably played a part in some ritual acts performed by the Orkney people until relatively recent times. Whilst their simple description doesn’t tell us this, the folklore of the adjacent body of water strongly suggests it. The stones were visited at the end of the 17th century by the antiquarian John Brand (1701) from whom we gain the only known account. He told that,

“At the north-east side of (St Tredwell’s) loch, nigh to the chapel, there is a high stone standing, behind which there is another stone lying hollowed in the form of a manger, and nigh to this there is another high stone standing with a round hole through it, for what use these stones served, we could not learn; whether for binding the horses of such to them as came to the chapel, and giving them meat in the hollow stone, or for tying the sacrifices to, as some say, in the times of Pagan idolatry, is uncertain.”

Several other hold stones are found in Orkney, some of which had lore that was thankfully recorded. We don’t know when these stones were torn down, but there is the possibility that they may have been cast into the loch alongside which they stood.

Folklore

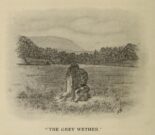

An intriguing piece of folklore relates to the adjacent St Tredwell’s Loch, right next to the stones. The loch was known of far and wide as possessing great healing properties which Mr Brand told to be distinctly pagan in nature. St Tredwell’s church had a cairn of stones by its side and those who visited here would pick one up and cast it into the loch as an offering (some folk would cast money), so that its waters would heal that person’s ailment. According to Brand and the local minister, such cures were numerous. The narrative is truly fascinating. Brand told us that,

“nigh to the east end of which this chapel is, is held by the people as medicinal, whereupon many diseased and infirm persons resort to it, some saying that thereby they have got good; as a certain gentleman’s sister upon the isle, who was not able to go to this loch without help, yet returned without it; as likewise a gentleman in the country who was much distressed wifh sore eyes, went to this loch, and washing there became sound and whole, though he had been at much pains and expense to cure them formerly. With both which persons he who was minister of the place for many years was well acquainted, and told us that he saw them both before and after the cure. The present minister of Westra told me that such as are able to walk, use to go so many times about the loch as they think will perfect the cure, before they make any use of the water, and that without speaking to any, for they believe that if they speak this will marr the cure: also he told that on a certain morning not long since he went to this loch and found six so making their circuit, whom with some difficulty he obliging to speak, said to him they came there for their cure.”

The reason that I’ve included this folklore to the site profile of the monoliths is that, at some time in the early past the stones would most almost certainly have played some part in the ritual enacted at the loch by which they stood. The building of Tredwell’s chapel was, quite obviously, an attempt to mark the place as christian in nature; but in such a remote region, old habits truly died hard. Of particular interest in the rituals described here is the element of silence. It’s fascinating inasmuch as it’s an integral ingredient in various ritual magick performances in different parts of the world. Even in some modern magickal rites, this is still vitally important. It’s a tradition also found at other lochs in Scotland and at lakes in many other parts of the world.

References:

- Brand, John, A Brief Description of Orkney, Zetland, Pightland Firth and Caithness, George Mosman: Edinburgh 1701.

- Royal Commission Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Inventory of the Ancient Monuments of Orkney and Shetland – volume 2, HMSO: Edinburgh 1946.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.