Enclosure & Stone: OS Grid Reference – SU 1285 7151

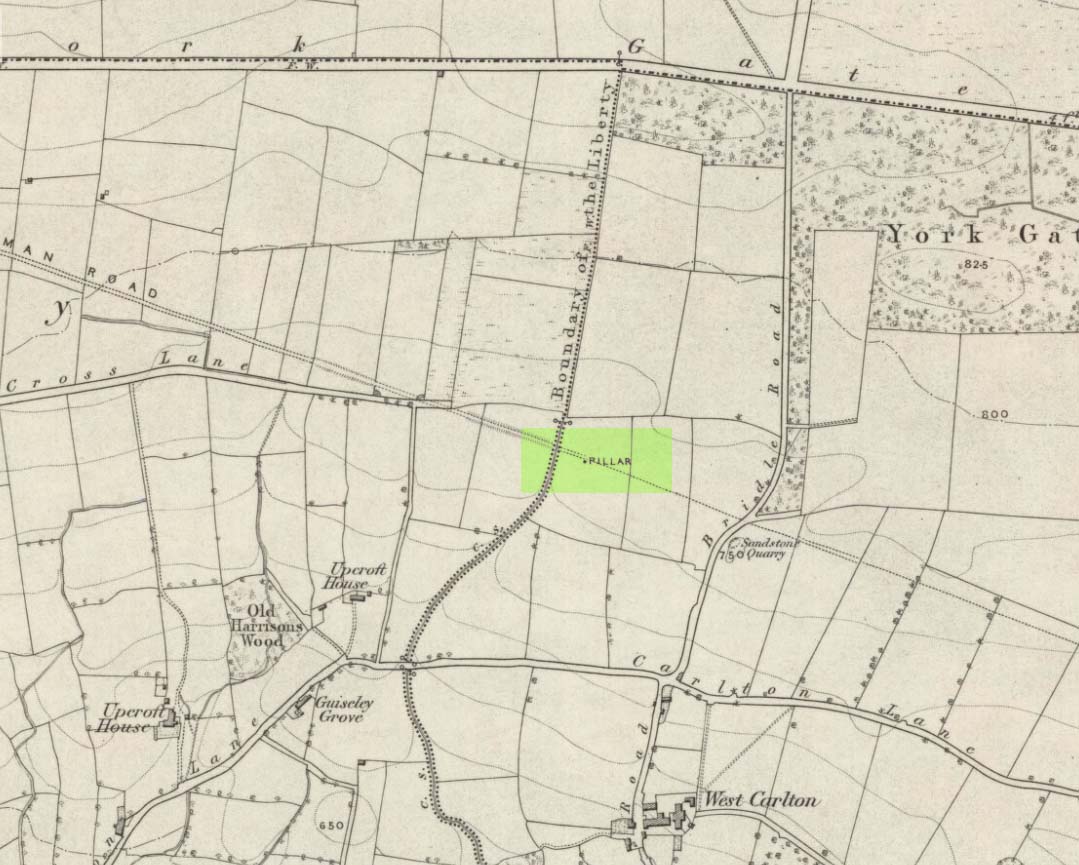

Follow the same directions to reach the Polisher Stone at the top-end of Overton Down as it meets Fyfield Down. From here, walk down the slope for 100 yards or so where you’ll notice, just above the long grassy level, a line of ancient walling running nearly east to west. It’s very close to the yellow marker in the attached aerial image shot to the right. If you walk along this line of walling you’ll find it.

Archaeology & History

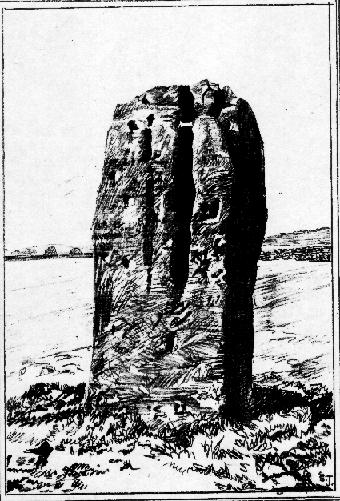

As I’ve only been here once, and briefly — under the guidance of the Avebury expert Pete Glastonbury — my bearings on this site may need revising. There are two distinct sections of walling here: one has been excavated by Peter Fowler and his team; the other hasn’t. (correct me if I’m wrong Pete) And in Fowler’s (2000) fine survey of this area he does not describe this very distinct holed-stone in the line of walling, or adjacent “linear ditch F4”, as it was called. But then, many archaeologists don’t tend to find items such as these of any interest (unless their education stretches to other arenas, which isn’t usually the case). But the stone seems to be in a section of walling that isn’t in their survey; standing out in aerial imagery as a less well-defined, but still obvious line of walling that is closer to the fence, 70-80 yards north, with a decidedly Iron-Age look about it!

But, precision aside! — as you can see in the photos, the holed stone here isn’t very tall — less than 2 feet high; though we don’t know how deep the stone is set into the ground. This spot is on my “must visit again” list for the next time we’re down here!

Folklore

There’s nowt specific to this stone, nor line of walling, nor settlement (as far as I know), but it seems right to mention the fact that in British and European folklore and peasant traditions, that holed stones just like the one found here have always been imbued with aspects of fertility — for obvious reasons. Others like this have also acquired portentous abilities; whilst others have become places where deeds and bonds were struck, with the stone playing ‘witness’ to promises made.

References:

- Fowler, Peter, Landscape Plotted and Pierced: Landscape History and Local Archaeology in Fyfield and Overton, Wiltshire, Society of Antiquaries: London 2000.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian