Souterrains & Settlement (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 577 572

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 43802

Archaeology & History

Overlee Farm in 1896 – no remains highlighted

This was an astonishing-sounding place, little-known beyond the pages of specialist historians. It has been described in modern terms as simply “subterranean structures”, “weems”, or “prehistoric underground houses”; but were this site still in evidence it would be a huge attraction! From the literary descriptions we possess, the extensive remains found and destroyed sound very much like the much-visited fogous found throughout Cornwall, or more commonly known as ‘souterrains’ in Scotland—although there’s no mention of the place in Wainwright’s (1963) singular study on such monuments. Despite this, here, on the south-side of modern Clarkston, it seems we once had a Renfrewshire equivalent to the prehistoric Cornish village and fogous known as Carn Euny.

The first known account of this site was written by James Smith (1845) in the survey for the New Statistical Account, who thankfully gave us a reasonably lengthy account of what was once here. He told:

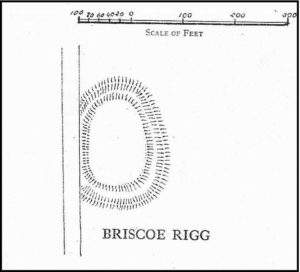

“About thirty years ago, on the farm of Overlee, which lies on the north bank of the river Cart, in the south-west angle of the parish, Mr Watson, the proprietor, on removing the earth from a quarry which he wished to open, discovered a great many subterraneous houses ranged round the slope of a small swelling hill. Each house consisted of one apartment, from eight to twelve feet square. The sides, which were from four to five feet high, were faced with rough undressed stone, and the floors were neatly paved with thin flag stones which are found in the neighbourhood. In the centre of each floor was a hole scooped out as a fire-place, in which coal-ashes still remained, and seemed to indicate that their occupiers had left the place on a sudden. That coal and not wood or peat had been employed as fuel, seemed at first an argument against the antiquity of the houses, until it was remembered that many seams of coal crop out on the steep banks of the river in the immediate vicinity, which may have been picked out for firing by the aboriginal inhabitants, as is still done to a limited extent by a few of the poorer classes in the neighbourhood. Near the fire-places were found small heaps of water-worn pebbles, from two to three inches in diameter, the use of which it is difficult to conjecture. They may have been used as missiles for attack or defence in the rude warfare of ancient days, or more probably they served the purposes of an equally rude system of cookery, by which meat was prepared for being eaten by heated stones placed round it, as is still done in many of the South Sea islands. The floors of the houses were covered to the depth of about a foot with a rich black vegetable mould, which was in all likelihood the decayed remains of the roofs mixed with soil filtered from the surface. As was gathered from the different appearances of the soil, in and over them, the houses were partly excavated from the hill and partly built above ground, and a level approach to the entrances was dug out of the slope. The number discovered amounted to forty-two, of which thirty-six formed the arc of a lower and larger circle, and the remaining six, also circularly ranged, stood a little higher up the hill. The writer is informed that the ruins of villages of a similar description have been discovered in several parts of Scotland; and there is an account of one very much the same as the above, recorded in the third volume of the Transactions of the Antiquarian Society of Scotland. About twelve querns or small hand-mills were found near the site of these houses, and a grave lined with stone containing a rude urn filled with ashes. These latter relics, however, may have belonged to a still distant but less remote antiquity. The old castle of Lee or Williamwood was erected near the place, and it is not improbable that, in procuring materials for the building from the freestone, of which the hill consists, the soil, which for so many centuries concealed the remains of the village, was thrown down upon it. Several years ago, the proprietor, in clearing away the old foundations of the castle, which interfered with the rectilineal operations of the plough, found within the square which they enclosed many human bones, which he avers were of almost superhuman magnitude.

“If the natives of the village, described above, deserted their homes hastily, as may be conjectured from the fact of the fuel remaining on their hearths, it may have been in terror of the Romans—one division of whose invading army must have passed not far from the place. In a direct north-east line from this hill, without any intervening eminence, and at the distance of about two miles, there are still very distinct traces of a small Roman encampment on the summit of a hill, the name of which, from the circumstance, is Camp Hill…”

Although the modern official description of these remains is simply that of “a settlement”, the idea that some of the remains here were souterrains seems beyond doubt. The comparison James Smith makes with remains that were found shortly afterwards that were “very much the same”, unearthed at Cairnconon—or the West Grange of Conon, as Canmore call it—northwest of Arbroath, confirms this idea.

Just over a decade after Mr Smith’s initial account, the Glaswegian historian James Pagan (1856), in his huge History of Glasgow, included another description of the place from the pseudonymous 19th century writer “J.B.” In what were called Desultory Sketches, much of what he wrote merely echoed the original notes by Smith, but they are still worth repeating:

“Specimens of the winter houses, or weems, were to be seen, till recently, in our own district, at Cartland Craigs, near Stonebyres, on the Clyde; and one very interesting example of the pit-houses was revealed in 1808, on the farm of Overlee, near Busby, in the vicinity of Glasgow. The following particulars regarding these were communicated to the writer of this sketch, by the parish minister of Cathcart, who had his information from an eye-witness.

“While the farmer was removing soil to get at freestone, for building a new steading, he came on a cluster of subterranean aboriginal huts. They were forty in number, and ranged round the face of the hill on which the farm-house of Overlee now stands. These huts were of the most primitive kind. They were mere semicircular pits, cut out of the hillside, with a passage to the door, also dug out of the slope, on a level with the floor, as indicated by the different colour of the soil. Each consisted of one small apartment, about twelve feet square, five feet high, and faced with stone. The floors were neatly paved with thin flag-stones, found in the neighbourhood. In the centre of each was a hole for a fireplace, in which ashes were still visible. Near the fireplace were small piles of water-worn stones, two or three inches in diameter, probably for cooking food, by placing heated stones round it, as is yet done by some of the islanders in the Pacific Twelve hand-querns of stone for grinding grain were found in the houses. At a short distance, a grave was discovered, lined with stone, and containing rude urns filled with ashes, thus indicating that the inhabitants of this primitive cluster, near what is now Glasgow, burned their dead. Unfortunately, the whole of these curious pit-houses were ruthlessly destroyed.

“In some of the weems and pit-houses, small groups of pretty oyster-shells have been found, perforated with small holes, as if they had been strung together, and formed an ornamental necklace—shall we say for the lady-savage of that distant epoch? In others were discovered bodkins and skewers, made of horn, probably to hold together the folds of the wild beasts’ skins forming the savages’ winter covering; the bones of oxen, neatly notched, as if for ornament; bowls made of stone, the hollow having been drilled out by the circular action of another stone, sharper and harder, aided by the grit of sand (one of which is now before me); arrow-heads and lances formed of flint or bone, some of the former of which I happen to possess; —nay, swords have been found, fashioned from the bone of a large fish! Heavy oaken war-clubs, too, must not be omitted from this curious catalogue.”

Although highly unlikely, there is the remote possibility that some remains of these underground ‘houses’, or souterrains, could possibly still be unearthed hereby. In recent years we’ve encountered a number of good farmers and land-owners who’ve told us about souterrains beneath their fields that are not in any record-books. Intriguingly, each one asked us, “who are you working for?” – and when we’ve assured them that we have nothing to do with the ‘official’ bodies, they’ve opened up and showed us. In one instance, a land-owner in Angus told us how he was farming the field as he’d always done, “when my tractor fell into a huge hole in the ground – and there was another souterrain!”

Why am I telling you this? Well, if you’re a local, maybe get round to Overlee and ask around some of the olde local people. You never know what you might find! And we could perhaps try find more about the other souterrain which the pseudonymous ‘J.B.’ said was “at Cartland Craigs, near Stonebyres, on the Clyde.”

References:

- McBeath, H.D., Walks by Busby and Thorntonhall, with Historical Notes on the Area, EKDC: East Kilbride 1980.

- Pagan, James (ed.), Glasgow, Past and Present – volume 2, David Robertson: Glasgow 1856.

- Ross, William, Busby and its Neighbourhood, David Bryce: Glasgow 1883.

- Smith, James, “Parish of Cathcart,” in New Statistical Account of Scotland – volume 7: Renfrew, William Blackwood: Edinburgh 1845.

- Stuart, John, “Notice of Underground Chambers recently Excavated on the Hill of Cairn Conan, Forfarshire,” in Proceedings Society of Antiquaries, Scotland – volume 3, 1862.

- Wainwright, F T., The Souterrains of Southern Pictland. RKP: London 1963.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.