Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – NC 56201 52713

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 5356

- Lochan Hakel A (Gourlay 1996)

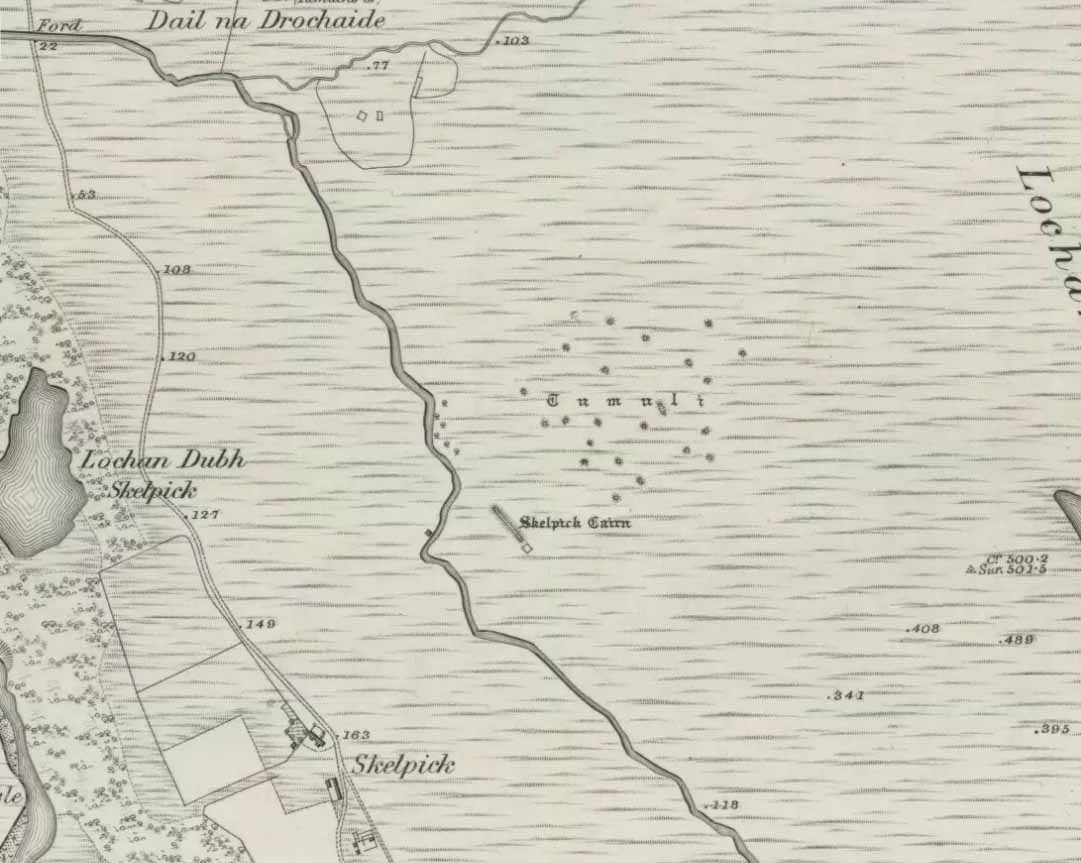

Whether you take the A836 or A838 into Tongue (through truly beautiful wilderness), make sure you go into the village itself—and then keep going, south, along the tiny country road for 3 miles. Hereby, keep your eyes peeled for Lochan na Cuilce on your right; keep going past here, into and through the old trees where you’ll then see Lochan Hakel on your left. Keep going past here until your reach the next small copse on your right. Stop here. A small pool is yards into the trees and here you’ll see a single stone between that and the roadside. You can’t really miss it!

Archaeology & History

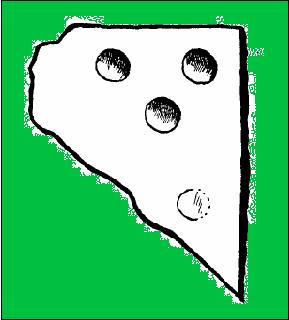

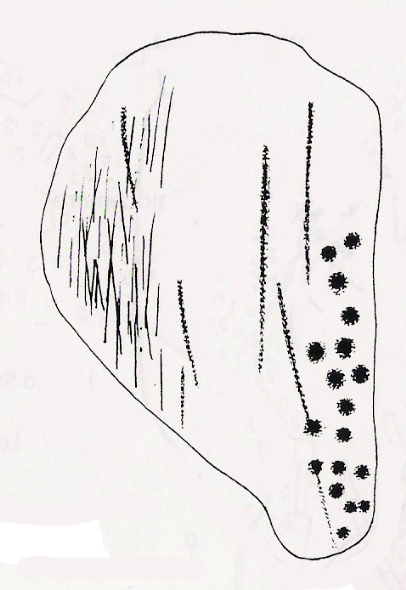

An apparently isolated cup-marked stone, some 3 feet by 5 feet, that was first described in Morrison’s (1883) meanderings amidst Sutherland’s awesome wilderness. It’s quite plain compared to Lochan Hakel 2 and many other carvings, simply consisting of 18 cups of various sizes, mainly on the eastern side of the rock. Sarah MacLean pointed out that a line running along the length of the stone seemed, in parts, to have been artificially enhanced by the hand of man, or woman. I have to agree with her.

The Royal Commission (1911) lads included this petroglyph in their superb survey of Sutherland, telling:

“On the W. side of the road to Kinloch, about ½ m. N of the bridge over the Kinloch River (Amhainn Ceann Locha), and on the N edge of a gravel pit close to the road, is a large earthfast boulder, 5′ in length as far as exposed, and 3′ 10″ in breadth, showing on its upper surface eighteen cup-marks of various depths, of which the most distinct is towards the N end of the stone, measuring about 3″ in diameter and 1″ in depth. The whole length of the stone is not visible, but the markings do not seem to extend to the portion covered…”

Simulacra lovers will love the form of this stone in relation to the background of the mountains, as its shape is echoed in that of the rising hills several miles to the south. …Of course, the depersonalizing ones amongst you lacking an understanding of animism would reject any such association due to your projection of disbelief. However—and equally—as we lack any ethnographic data on the carving we must also assume some caution…

A fascinating site – and one which is likely to have neighbours hidden in the surrounding moorlands…

References:

- Gourlay, Robert, Sutherland: An Archaeological Guide, Birlinn: Edinburgh 1996.

- Michell, John, Simulacra, Thames & Hudson: London 1979.

- Morrison, Hew, Tourist’s Guide to Sutherland and Caithness, D.H. Edwards: Brechin 1883.

- Royal Commission on Ancient & Historical Monuments, Scotland, Second report and inventory of monuments and constructions in the county of Sutherland, HMSO: Edinburgh 1911.

Acknowledgments: Huge thanks to Donna Murray for use of her photos in this site profile (aswell as for putting up with me whilst in the area); and also to Sarah MacLean for taking us to the carving in the first place. Many many thanks indeed. See y’ again soon, hopefully!

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.