Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NS 56413 99540

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 44622

- Gartrenich

- Milling

- Menteith 1

Getting Here

Peace Stone cup-and-ring

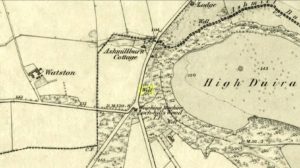

The quickest way here is bedevilled with troublesome parking (and an unhelpful local at Malling Cottage). That aside, roughly halfway along the A81 between the Braeval roundabout (near Aberfolye) and Port of Meneith, turn down the track at Malling, following it round for 300 yards through the farm, then another 500 yards or so until you reach a junction with a gate on your left. Walk down the track to your right, roughly alongside the Lake of Menteith, for nearly 700 yards until you reach the gate into the forestry commission land. Go thru the gate and turn immediate right, following the fence for about 200 yards where a clump of stones lives. You’re there!

Archaeology & History

The Peace Stone in 1899

This seemingly isolated petroglyph, known about by local people in the middle of the 19th century and earlier, was said to have been “held in great reverence.” It was first mentioned in literary accounts in 1866, when the oral traditions about it were more important than any archaeocentricism. But things change with the times: local people were kicked off their lands, old stories and knowledge of sites were lost, and the ‘discipline’ of archaeology was beginning to look at these curious carved rocks with puzzled minds.

The Peace Stone was described at some length and with considerable accuracy in Mr A.F. Hutchison’s (1893) gazetteer on the ancient stones of Stirlingshire. It was one of the regions only known petroglyphs at that time and thankfully he gave us a good account of it, saying:

“On the west ride of the Lake of Menteith, about half a mile south from the farm-house of Malling, this stone is to be found, lying at the boundary of the arable land. The ground at the place rises into a slight eminence, on the top of which the stone lay till some seven or eight years ago, when a labourer took it into his head that a stone on which so much labour had evidently been spent must have been intended to cover something valuable. He proceeded to excavate the earth at the side with the intention of getting at the buried treasure, with the result that the stone slipped down into the hole which he had made, where it now lies. It is quite possible, however, that an interment, if no treasure, might be found beside it on further research. The stone is roughly circular on the surface, measuring about 4 feet in diameter. It is entirely covered with cup and ring marks—22 cups in all—varying in size from an inch to two inches in diameter. The cups and rings are very symmetrically formed. Nearly in the centre is a fine one surrounded by four circular grooves. Others have incomplete triple and quadruple circles, with radial duct dividing them. There are other curious curves that sometimes interlace, and near the lower side of the stone are five or six cups with straight channels running out from them over the edge. This is an extremely interesting stone. It is unique in our neighbourhood, so far as I know, in showing these symmetrical carvings. They are now, however, much weather-worn.”

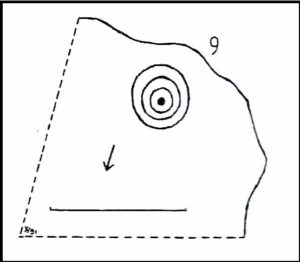

Ron Morris’ sketch & photo

When Alison Young (1938) came to write about the carving, she echoed Hutchison’s thought that the stone might originally have covered a tomb—but we simply don’t know and it should be treated as guesswork, as there are no known prehistoric tombs anywhere hereby.

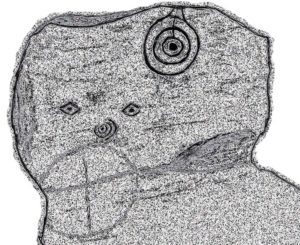

Close-up of faded cups

Years passed before the next archaeological visit – by which time the stone had been uprooted and moved, apparently “ploughed up by the Forestry Commission”, and when Ron Morris (1981) last sought it out found that “the stone was un-traceable”. On a previous visit, before being moved, he found it to be,

“a cup-and-three-rings, 3 cups surrounded by two rings…and 6 cup-and-one-ring. One of these and 2 cups form part of the design of the cup-and-three-rings. There were also at least 7 other cups, and a number of grooves, some forming lines from a central cup, or a cup-mark, downhill. Greatest diameter visible in 1977 30cm (12in) and depth of carving 3cm (1 in)… Many of the carvings are so weathered as to be visible only when wet in early morning or late evening.”

And when we visited the site a few days ago, the stunning sunlight that had followed us all day, sadly faded and disallowed us better photographs of the site. Huge apologies…. But it’s worth visiting when the daylight’s good, perhaps when you’re exploring the huge number of brilliant petroglyphs at Ballochraggan and Nether Glenny on the hillside 1½ miles immediately north of this “outlier”, as Brouwer & van Veen (2009) called it.

Folklore

In a landscape bedevilled with stunning petroglyphs, traditions and folklore of them is all but gone; but the story of the Peace Stone was thankfully captured in words by Mr Dun (1866), who told us:

There is a curious prophecy connected with a stone situated near the ruins of the chapel of Arnchly, and which is worth recording. From time immemorial this stone went under the name of the Peace Stone, and it was held in great reverence by the natives. One Pharic McPharic, a noted Gaelic prophet, foretold that, in the course of time, this stone would be buried underground by two brothers, who, for their indiscretion, were to die childless. By-and-by the stone would rise to the surface, and by the time it was fairly above ground, a battle was to be fought on “Auchveity,” that is, “Betty’s Field.” The battle was to be long and fierce, until “Gramoch-Cam” of Glenny, that is, “Graham of the one eye,” would sweep from the “Bay-wood” with his clan and decide the contest. After the battle, a large raven was to alight on the stone and drink the blood of the fallen. So much for the prophecy then; now for the fulfilment. About fifty years ago, two brothers (tenants of the farm of Arnchly), finding that the stone interfered with their agricultural labours, made a large trench, and had it put several feet below the surface. Very singular, indeed, both these men, although married, died without leaving any issue. With the labouring of the field for a number of years, the stone has actually made its appearance above ground, and there is at present living a descendant of the Grahams of Glenny who is blind of one eye, and the ravens are daily hovering over the devoted field. Tremble ye natives! and rivals of the “Hero Grahams,” keep an eye on Gramoch-Cam!

The name of Betty’s Field came from an earlier piece of folklore: where a prince out hunting a stag was caught in one of the deep bogs hereby, only to be rescued by a local lass. In return for her help, she was given a large piece of land which was to bear her name.

References:

-

Armit, Ian, “The Peace Stone (Port of Menteith parish),” in Discovery & Excavation Scotland, 1998.

- Brouwer, Jan & van Veen, Gus, Rock Art in the Menteith Hills, BRAC 2009.

- Dun, P., Summer at the Lake of Monteith, James Hedderwick: Glasgow 1866.

-

Hutchison, A.F., “The Standing Stones and other Rude Monuments of Stirling District,” in Transactions Stirling Natural History & Antiquarian Society, volume 15, 1893.

-

Hutchison, A.F., The Lake of Menteith: Its Islands and Vicinity with Historical Accounts of the Priory of Inchmahome and the Earldom of Menteith, Stirling 1899.

- Mallery, Garrick, “Pictographs of the North American Indians,” in Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, volume 4, 1886.

- Morris, Ronald W.B., The Prehistoric Rock Art of Southern Scotland, BAR: Oxford 1981.

- van Hoek, Maarten, “Menteith (Port of Menteith parish) Rock Art Sites,” in Discovery Excavation Scotland, 1989.

-

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.