Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – NN 57047 02878

Along the A81 road from Port of Menteith to Aberfoyle, watch out for the small road in the trees running at an angle sharply uphill, nearly opposite Portend, up to Coldon and higher. Keep going, bearing right past Mondowie and stopping at the dirt-track 100 yards or so further up on the left (ignore the english fuckers up here who tell you it’s a pwivate road and they don’t want you parking there—unless you’re blocking the road obviously!). Walk up up here for ⅔-mile, as if you’re visiting the Over Glenny (5) carving, but as you get close to the defining sycamore tree, walk past it for about 60 yards towards the ruinous buildings. You’re looking for a reasonably large earthfast rock with a notable bowl about 12-inch across at the edge of the stone. That’s your defining feature.

Archaeology & History

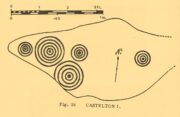

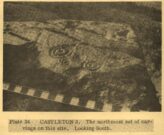

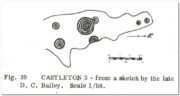

This is another decent design in the mass of petroglyphs on this plain overlooking the Lake of Menteith. On our first visit here ten yeas ago, only one half of the rock was visible—and half of that was covered with grasses! But with patience, we slowly rolled back the turf and slowly uncovered more and more, eventually seeing the main elements you can see in these photos and the arty sketch I’ve made here. (the Over Glenny [14] carving a few yards further east may be just be a continuation of this design)

When the carving was first noticed by George Currie (2010), he only noticed “a cup mark surrounded by two penannulars, an arc and a single radial”—ostensibly meaning, a cup-and-triple ring, with the outer ring incomplete, and a line running out from the central cup. But there’s more, obviously. On our second visit, a very faint but distinct cup-and-double-ring was noticed in low light on the same section of the rock where the triple-ringed element is carved. We weren’t able to get a photo that showed it, as the light wasn’t doing as we needed, but I’ve highlighted it on the sketch, where it’s to the right of the large ‘bowl’ at the very edge of the rock. This ‘bowl’ probably had utilitarian functions, whether it was for just crushing herbs or grains, or to make organic paints: and this function most likely had some relationship with the petroglyph—but we know not what! It’s possible that the people who lived in the adjacent ruin, several centuries ago, may also have made use of this.

When we exposed the other half of the carving, a very well-cut and well-preserved cup-and-ring sat beside another much more eroded partner, which was almost impossible to see from some angles. You can just make it out in the photos here. You’ll also notice a scatter of several other cup-marks and elongated ‘cups’ on the same section of rock. It was difficult to work out whether some of these marks in the stone were Nature’s handiwork, or the result of human hands. Some were obviously man-made, but we need to look at it again when the daylight conditions are good, so that we can make a more accurate assessment.

References:

- Brouwer, Jan & van Veen, Gus, Rock Art in the Menteith Hills, BRAC 2009.

- Currie, George, “Port of Menteith: Upper Glenny (UG 1), Cup-and-Ring Marked Rocks”, in Discovery & Excavation, Scotland, New Series – volume 11, 2010.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to the crew: Paul Hornby, Lisa Samson & Fraser Harrick in making this carving come to life, and for use of a photo or two.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.