Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NS 5519 6020

Also Known as:

- St. Ninian’s Well

Archaeology & History

This all-but-forgotten holy well was becoming nothing but a faded memory even in the middle of the 19th century. Excluded from all of the previous Scottish holy well surveys, the site is mentioned in George Campbell’s Eastwood (1902) where, in his description of the obscure saint, St. Conval or Convallus—to whom Eastwood parish was dedicated—the position of the well is mentioned. When St. Conval first came to the area, said Campbell,

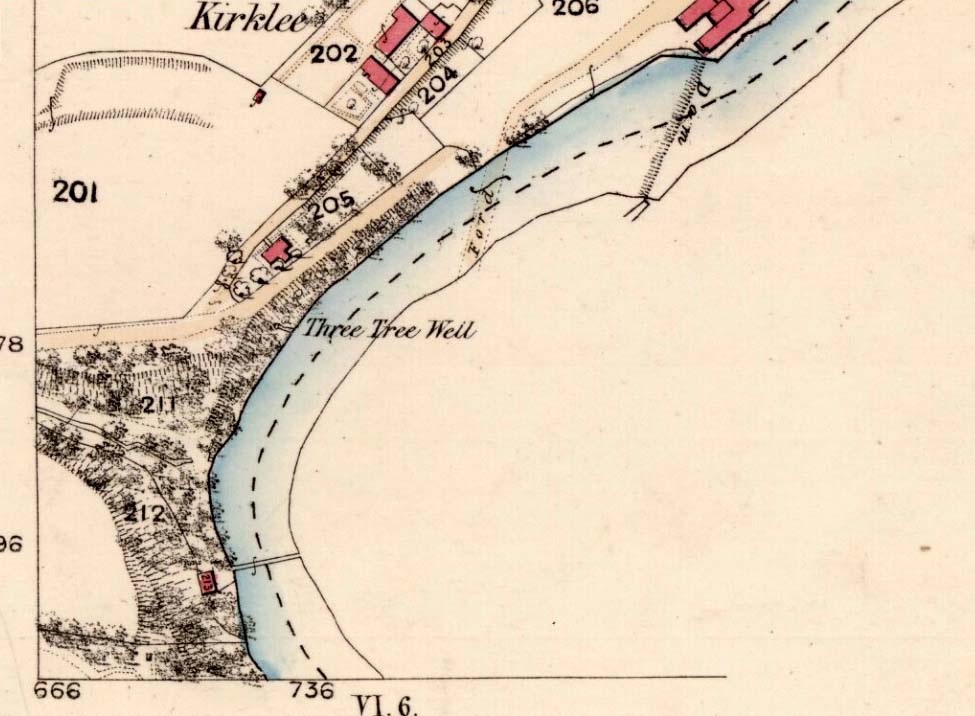

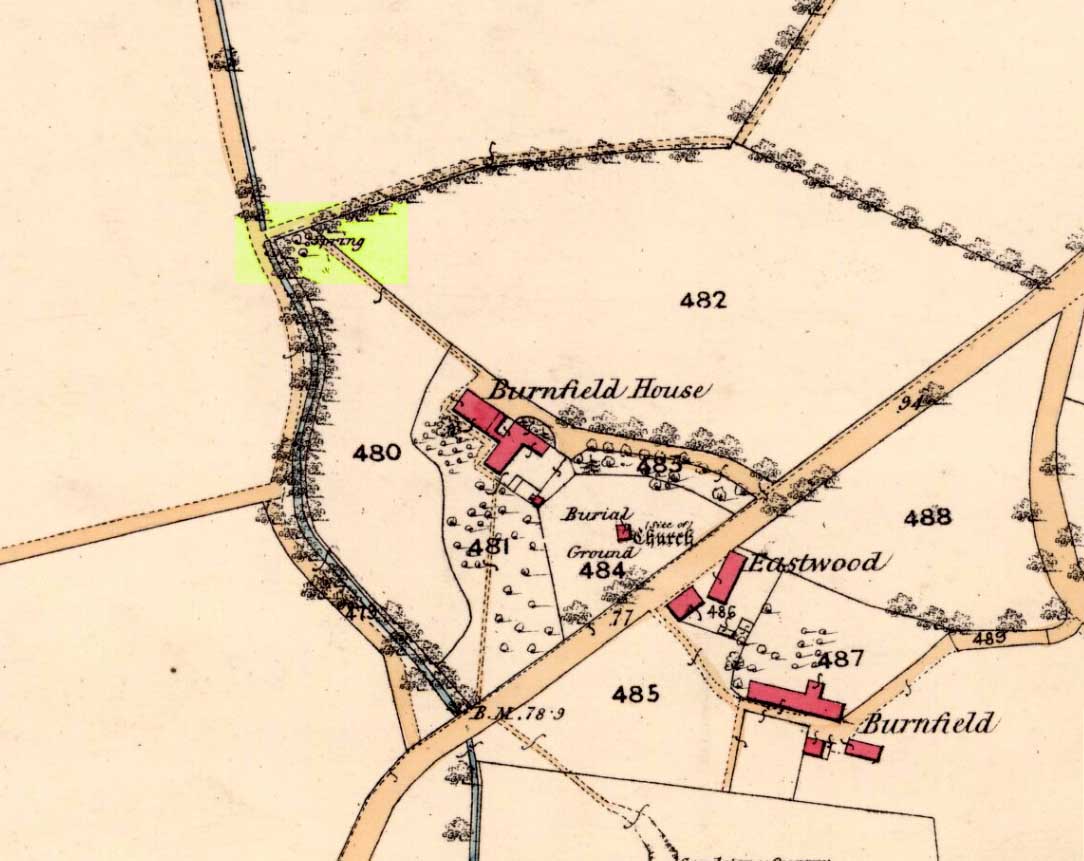

“The particular spot which the saint selected for his cell would be determined, as was so commonly the case, by the then remarkable spring which can still be traced in the lower part of what was the glebe before the excambion in 1854. Within the memory of man, even of my own, as I resided for a year in the old manse, before its removal from the early site, this well, as stated in the last Statistical Account, discharged about eleven imperial pints a minute, and was perennial, affected neither by drought nor rain. Up to that date the water was sufficiently abundant to supply the manse and all the families in what was still a bit of a hamlet, the remains of the Kirkton, as it was formerly called. But coincident to the removal of the last living remains of an ecclesiastical establishment from the spot, it has well nigh dried-up, through disturbances caused, it is believed, by the working of pits and quarries in the neighbourhood; but it is confidently hoped that what remains of it may be preserved, and a memorial erected over it of the long-departed past, situated as it is within the enclosure of the now extended burial ground. There can be no doubt that in its waters our fathers were baptised when they renounced Druidism, or whatever was their pagan form of faith, and a sacredness would thus naturally attach to it in former times…”

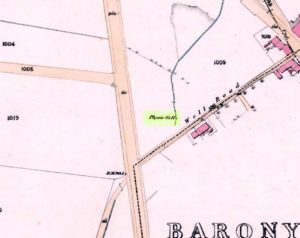

When we sought out this well in the furthest corner of the old churchyard—where Ordnance Survey placed the ‘Spring’ on the 1863 map—we were greeted by a completely dried-up site, long since fallen back to Earth, with little hope of it ever resurfacing unless good local people choose to do something. The well was surrounded by excrement and litter and it truly needs a good clean-up and a dig down to bring the waters back to the surface.

In an Appendix to Campbell’s Eastwood, he tells that he came across a map-reference to the site, where it was shown as “St. Ninian’s Well”, but I have been unable to locate this.

References:

- Bennett, Paul, Ancient and Holy Wells of Glasgow, TNA 2017.

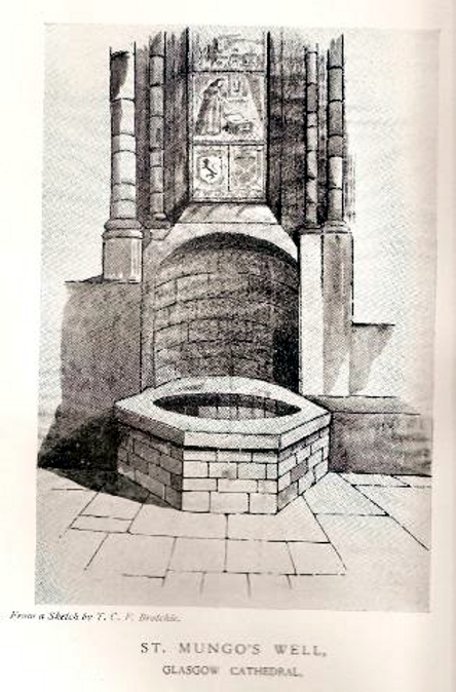

- Brotchie, T.C.F., “Holy Wells in and Around Glasgow,” in Old Glasgow Club Transactions, volume 4, 1920.

- Campbell, George, Eastwood: Notes on the Ecclesiastical Antiquities of the Parish, Alexander Gardner: Paisley 1902.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Paul Hornby & Nina Harris for helping to locate the spot where this old well once existed.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.