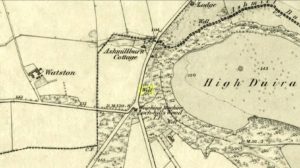

Sacred Well (lost): OS Grid Reference – NN 27 81

Also Known as:

- St Bride’s Well

Archaeology & History

This long lost ‘holy well of St Brigit’ (Tobar Bhride) has been mentioned—purely in literary repetition—by such folklore giants as F.M. MacNeill and others, but none of them give any additional information about it than that first mentioned by Alexander Stewart’s (1890) in his fascinating article on magical stones. Indeed, knowledge of this well’s very existence was only preserved thanks to a ritual incantation that was recited to imbue and maintain healing properties of one such magickal stone, known as the Charm Stone of Keppoch. It

“was an oval of rock crystal, about the size of a small egg, fixed in a bird’s claw of silver, and with a silver chain attached, by which it was suspended when about to be dipped.”

It was dipped in water taken from the sacred well of St Brigit, somewhere not far from Keppoch. The incantation made over the stone was in Gaelic, obviously, but the english translation is:

“Let me dip thee in the water,

Thou yellow, beautiful gem of Power!

In water of purest wave,

Which (saint) Bridget didn’t permit to be contaminated.

In the name of the Apostles twelve,

In the name of Mary, virgin of virtues,

And in the name of the high trinity

And all the shining angels,

A blessing on the gem,

A blessing on the water, and

A healing of bodily ailments to each suffering creature.”

On the east side of the river, just a few hundred yards away, could once be found the Fuaran na Ban-Tighearna, or the Well of Her Ladyship. In this sense, the term ‘ladyship’ refers to the “wife of a baronet or knight.” (Dwelly 1918) The idea that it may refer to Bride in Her guise as a ‘lady’ is linguistically improbable here (though not impossible). Also, if this fuaran did have a geomythic relationship with Bride, we would expect to find a Cailleach in the nearby landscape, which we don’t.

Folklore

An interesting piece of folklore that may relate to this well is described by the great Scottish landscape wanderer, Seton Gordon. (1948) Although he makes no mention of a Bride’s Well, there is the tale of a missing bride up Glen Roy, of which Keppoch sits below. “It was in earlier times,” he wrote,

“that the Maid of Keppoch was taken by the fairies in Glen Roy. She was an Irish girl, little more than a child, and had become the wife of MacDonell of Keppoch. But the wedding rejoicings were scarcely over when the bride, wandering into the oak woods which still clothe the lower slopes of Glen Roy, disappeared mysteriously. It was believed that, like the Rev Robert Kirk…she had been spirited away by the fairies. If indeed she was abducted by the Little People they held her closely, for from that day to this no trace has been found of the fair Maid of Keppoch.”

St Bride of course was Irish, like the Maid of Keppoch. And just a mile up Glen Roy from Keppoch House we find the Sron Dubh and Sithean, or Ridge of the Dark Fairy Folk. There are several burns (streams) running either side and below this fairy haunt, but I can find none with Bride’s name. Someone, somewhere, must know where it is…

References:

- Gordon, Seton, Highways and Byways in the Central Highlands, MacMillan: London 1948.

- Dwelly, Edward, The Illustrated Gaelic English Dictionary – volume 1, Fleet Hants 1918.

- Stewart, Alexander, “Notice of a Highland Charm-Stone,” in Proceedings Society Antiquaries, Scotland, volume 24, 1890.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian