Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SD 555 335

Also Known as:

- Holy Well

- Lady’s Well

- St. Mary’s Well

The well can be reached along a narrow country lane to the east of the A6 road, some 3-4 miles north of Preston. Fernyhalgh is a tiny hamlet between the villages of Broughton and Grimsargh with pleasent countryside on all sides. The holy well of Our Lady is in the garden of a house with a Roman Catholic chapel and pilgrimage centre at the side of a secluded country lane; entrance through a little gate.

Archaeology & History

There was a chapel on this site way back in 1348, and the spring itself is obviously a pre-Christian one with its dedication to Our Lady – St Mary the Virgin. According to the legend, in about 1471 a merchant sailing across the Irish sea was caught in a terrible storm; afraid that he was going to drown he prayed to the Virgin Mary and vowed that if his life was saved he would undertake some work of devotion to her. Soon the storm cleared and he found himself washed-up but safe on the Lancashire coast but he himself had no idea where he was. At that moment a heavenly voice spoke to him and told him to find a place called Fernyhalgh and there build a chapel at a spot where a crab-apple tree grew – the fruit of which had no cores, and where a spring would be found. He began to search around for this sacred place but no matter how much he tried he could not find the place.

The merchant found lodgings in Preston and, was about to give up altogether, when he overheard a serving girl at the inn. She started to explain why she was so late on arrival. She went on to say that she had had to chase her stray cow all the way to Fernyhalgh. He asked her if she could take him to this place. In a short time he discovered the apple tree with fruit bearing no cores and beneath it a spring and also a lost statue of the Virgin and child. The merchant began to build a chapel close by in memory of Our Lady and soon pilgrims were visiting the holy well and receiving miracles of healing. However, during the time of persecution from the reign of King Henry VIII and through to the reign of King Edward VI the well was abandoned and left derelict; the chapel itself was demolished.

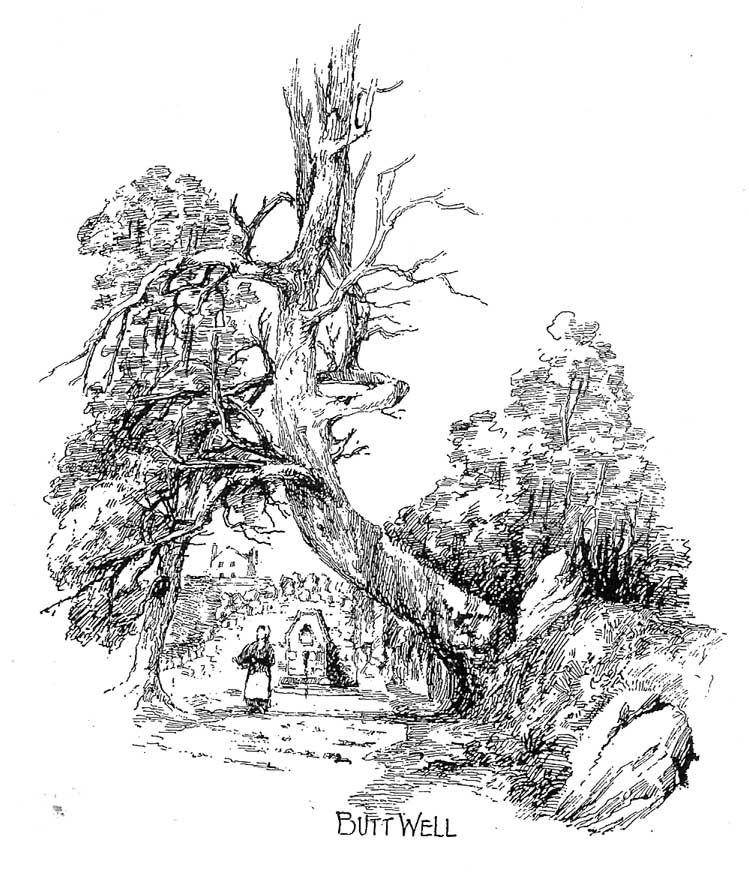

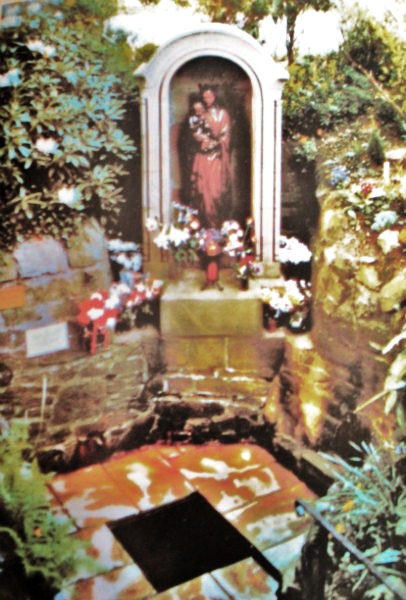

The holy well of Our Lady was fully restored in the late 17th century and a new chapel was built in 1685 when persecutions towards Catholics had eased. Again, the place became a place of pilgrimage and many miraculous cures were being recorded there; the chapel (which is now built onto a house) being used by religious sisters as a place of retreat. Today it is a renowned Roman Catholic pilgrimage centre with thousands of visitors coming from far and wide. The holy well stands within a rectangular enclosure with steps descending down; the well itself being a small-square shaped basin overlooked by a niche inside which stands the Virgin Mary holding baby Jesus. It is very well cared for by the Catholic community with flowers usually adorning the site during the Summer months. Coins are often thrown into the well, though it is not regarded as a “wishing well”. Visitors are always welcome and, you don’t have to be a Catholic, everybody regardless of what persuasion you are can visit the well.

References:

- Bord, Janet & Colin, Sacred Waters, Paladin Books 1986.

- Fields, Ken, The Mysterious North, Countryside Publications.

- Taylor, Henry, The Ancient Crosses and Holy Wells of Lancashire, Sherratt & Hughes: Manchester 1906.

© Ray Spencer, 2011