Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SK 4378 3861

Dale Abbey is a small and interesting village not far from Ilkeston. It can be found by taking the A6096 from Ilkeston and after passing through Kirk Hallam, take the first turning on the left called Arbour Hill. At the Carpenter’s Arms in the village turn right and park near the church. The well lies within the private garden of Church house, although it can be easily seen in the winter from the field in which the footpath below the church passes through, as well from the church yard.

Archaeology & History

R.C. Hope (1893) gives two versions of the story of how the hermit found the well and cave, taken from the Chronicle of Thomas de Musca quoted in Glover’s History of Derbyshire:

“A hermit once going through Deep Dale being very thirsty, and for a time not able to find any water, at last came upon a stream, which he followed up to the place where it rose; here he dug a well, returned thanks to the Almighty, and blessed it, saying it, should be holy for evermore, and be a cure for all ills. Another version is that the famous Hermit of Deep Dale, who lived in the Hermitage which is close by the well, discovered this spring and dug the well, which never dries up, nor does the water diminish in quantity, however dry the season and blessed it.”

In another version of the story, Hope (1893) notes:

“There was a baker in Derby, in the street which is called after the name of St. Mary. At that period the church of the Blessed Virgin at Derby was at the head of a large parish, and had under its authority a church de onere and a chapel. And this baker, otherwise called Cornelius, was a religious man, fearing God, and, moreover, so wholly occupied in good works and the bestowing of alms, that whatsoever remained to him on every seventh day beyond what had been required for the food and clothing of himself and his, and the needful things of his house, he would on the Sabbath day take to the church of St. Mary, and give to the poor for the love of God, and of the Holy Virgin. It happened on a certain day in autumn, when he had resigned himself to repose at the hour of noon, the Blessed Virgin appeared to him in his sleep, saying, ” Acceptable in the eyes of my Son, and of me are the alms thou hast bestowed. But now, if thou art willing to be made perfect, leave all that thou hast, and go to Depedale where thou shalt serve my Son and me in solitude; and when thou shalt happily have terminated thy course thou shalt inherit the kingdom of love, joy, and eternal bliss which God has prepared for them who love Him. The man, awakening, perceived the divine goodness which had been done for his sake; and, giving thanks to God and the Blessed Virgin, his encourager, he straightway went forth without speaking a word to anyone. Having turned his steps towards the east, it befel him, as he was passing through the middle of the village of Stanley, he heard a woman say to a girl, ”Take our calves with you, drive them as far as Depedale, and make haste back.” Having heard this, the man, admiring the favour of God, and believing that this word had been spoken in grace, a, it were, to bin’, was astonished, and approached near, and said, “Good woman, tell me, where is Depedale?” She replied, “Go with this maiden, and she, if you desire it, will show you the place. When he arrived there, he found that the place was marshy, and of fearful aspect, far distant from any habitation of man. Then directing his steps to the south-east of the place, he cut for himself, in the side of the mountain, in the rock, a very small dwelling, and an altar towards the south, which hath been preserved to this day; and there he served God, day and night, in hunger and thirst, in cold and in meditation.

And it came to pass that the old designing enemy of mankind, beholding this disciple of Christ flourishing with the different flowers of the virtues, began to envy him, as he envies other holy men, sending frequently amidst his cogitations the vanities of the world, the bitterness of his existence, the solitariness of his situation, and the various troubles of the desert. But the aforesaid man of God, conscious of the venom of the crooked serpent, did, by continual prayer, repeated fastings, and holy meditations, cast forth, through the grace of God, all his temptations. Whereupon the enemy rose upon him in all his might, both secretly and openly waging with him a visible conflict. And while the assaults of his foe became day by day more grievous, he had to sustain a very great want of water. Wandering about the neighbouring places, he discovered a spring in a valley not far from his dwelling, towards the west, and near unto it he made for himself a cottage, and built an oratory in honour of God and the Blessed Virgin. There, wearing away the sufferings of his life, laudably, in the service of God, he departed happily to God, from out of the prison-house of the body.”

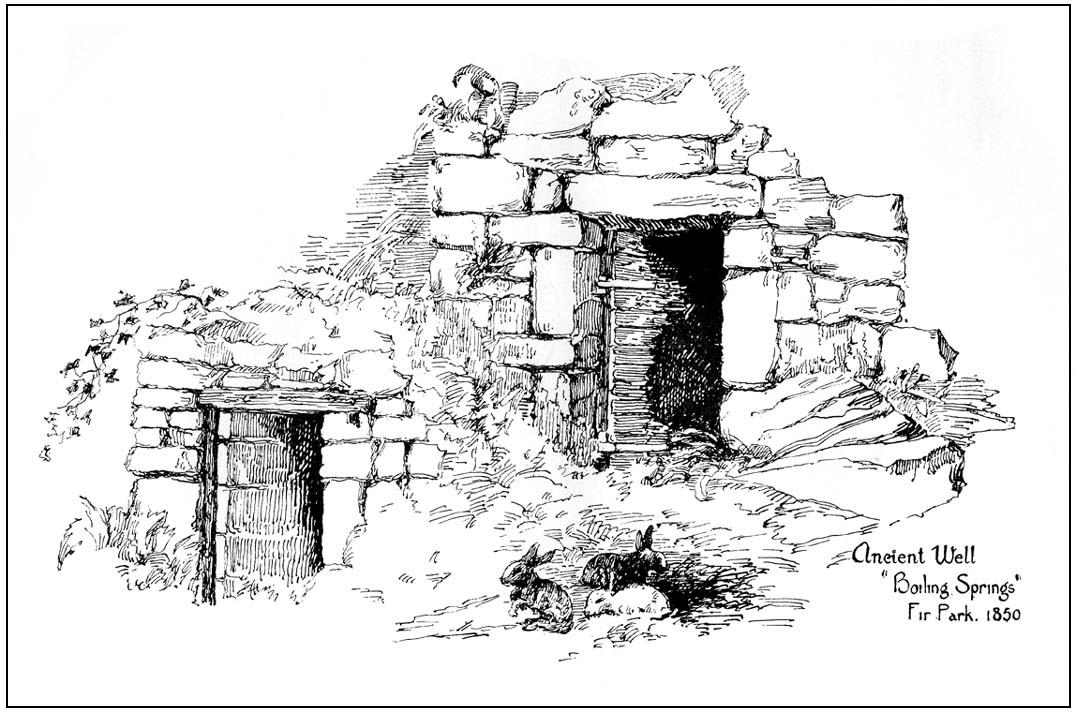

The well is a delightfully rustic one and certainly contains old stonework if not from the hermit’s time than the period of the Abbey. It is an oval structure with eight stones around the mouth, a three foot rectangular stone covers half of the well and has a semi-circular cut placed in the middle. Mossy steps lead from the higher end of the garden into the little dell where the well arises. The well has been dressed in the early 2000s but has now disappeared into obscurity. Indeed, some believe that it is does not exist in the first place…

Folklore

First noted in 1350 in association with the legend of the foundation of the Abbey, Hope (1893) notes it was curative and was a wishing well; being visited on Good Friday, between twelve and three o’clock, water being drunk three times.

References:

- Hope, Robert Charles (1893), Legendary Lore of the Holy Wells of England, Elliott Stock: London.

- Parish, R.B. (2008), Holy wells and healing springs of Derbyshire.

Copyright © Ross Parish