Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – NN 9376 0719

Also Known as:

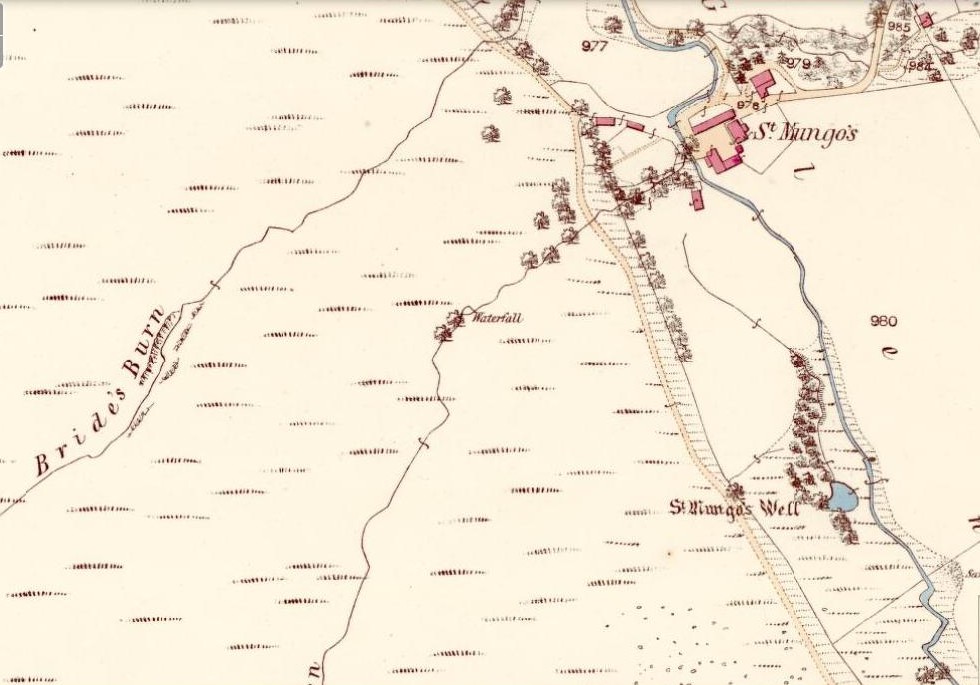

The best way here is to walk a mile to find it. All the way up the road from Gleneagles Standing Stones to Glendevon, right at the very top where the two glens meet, there’s a small road heading to the Fishery. 100 yards along, park up. Then take the old green road back down the Glen, north towards Gleneagles, parallel with the new road. A mile or so down you’ll reach the farmhouse, but a coupla hundred yards before this, in a wooden gap in the electric fence, you can walk straight downhill to the large pool below you. Y’ can’t really miss it!

Archaeology & History

The strong cold spring of water known as St Mungo’s Well, now gathers into a large crystal clear pool and is gorgeous to drink and very refreshing! All around the edges are the brilliant yellow masses of gorse, held amidst widespread vivid hues of green in this most rocky of landscapes. Tis a gorgeous setting here….

Unfortunately there is no literary information that tells us why this spring of water, amongst the many others all around these hills, gained the ‘blessing’ of one of those roaming christians and was deemed to be ‘holy’. The greatest likelihood, as usual, is that the waters had some important heathen association which our peasant ancestors would have been able to tell us about if their animistic tales hadn’t been outlawed and demonized by the incoming cult — but we’ll probably never know for sure. As a result, we know nothing now of its medicinal qualities or old stories.

The transference of its old name (whatever it may have been) to their ‘St. Mungo’ may date from when the character was wandering with his christians in the 7th century, but we have no literary account proving as such. The name ‘St Mungo’ was an alternative name (a nickname if y’ like) of St. Kentigern — or at least that’s what the church historians tell us. There is no history of Kentigern or St Mungo up the glen, but we do have a more prosaic account that tells of a Mr Mungo Haldane of Gleneagles, a member of the Scottish parliament in 1673 onwards; he was succeeded by another Mungo Haldane MP in 1755. However, it’s highly unlikely that these political characters gave their name to the well.

Even the Scottish holy wells surveys are pretty silent on this beautiful site. It was mentioned in Morris’ (1981) survey, but with no real information. The earliest account seems to come from an article written in the Perthshire Advertiser in 1856, and thankfully reproduced in the otherwise tedious genealogical history of the Haldane (1880) family; but even here, the narrative simply mentions the presence of the well and no more. Described in a walk up Gleneagles, it told:

“Journeying westward along the desolate moor…we soon came in front of Gleneagles, a narrow picturesque glen in the Ochils, through which the old road from Crieff leads into Kinross-shire. The hills here, as throughout the whole range, are strictly pastoral, but in no place more so than Gleneagles. Crowning the heights on both sides of the glen, we have craigs ragged and bare enough; but their show of beetling hard sterility is as nothing to the winding receding mass of grassy heights that bound the view. In looking on that quiet, sunny, Sabbath-like retreat, one would be apt to deem the name a misnomer, and yet it is not much above a hundred years since the monarch of birds had a home among its cliffs. There, too, the Ruthven Water that dashes past Auchterarder has its rise — not in a scarcely seen bubbling spring almost covered with moss, but issuing at once into daylight at the bottom of yonder steep in volume sufficient to drive a mill. In ancient times, as now, it must have been an object of mark, as it is called St. Mungo’s Well; but who this St. Mungo or St. Magnus was — whether the ghostly patron of Glasgow, Auchterarder old chapel, or the guardian saint of this particular spot, we cannot tell. But he seems to have relished cold water; and it is satisfactory to know that he must have got his fill of it there, if his cell happened to be in the vicinity.”

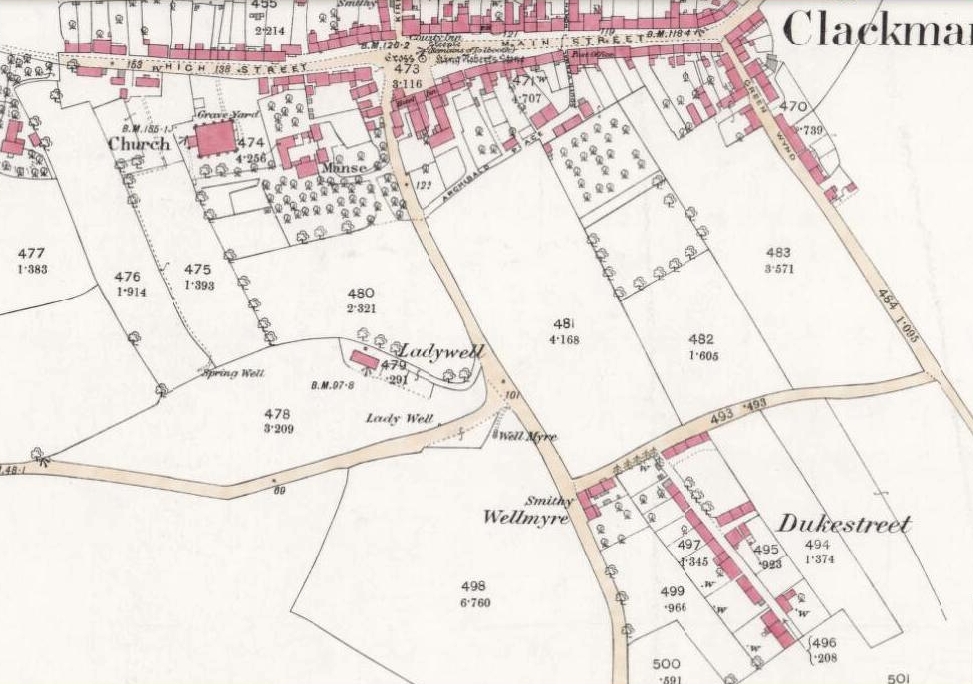

The well was mentioned in passing in the Object Name Book in 1860 and shown on the earliest Ordnance Survey maps.

Folklore

Apart from the fact that the waters here never run dry, we have no other folklore. However it should be noted that St. Mungo’s Day was January 14th — which may have been when the qualities of the spring were deemed most efficacious, or when olde rites were enacted here. However, a hundred yards down we pass the stream known as Bride’s Burn, probably in honour of the heathen Queen St. Brigit, whose name and myths are integral to our great Earth goddess, the Cailleach and whose celebration date is only two weeks later than that of Mungo. Hmmmmmmm…..

References:

- Attwater, Donald, Penguin Dictionary of Saints, Penguin: Harmondsworth 1965.

- Haldane, Alexander, Memoranda Relating to the Family of Haldane of Gleneagles, C.A. MacKintosh: London 1880.

- MacKinlay, James M., Folklore of Scottish Lochs and Springs, William Hodge: Glasgow 1893.

- Morris, Ruth & Frank, Scottish Healing Wells, Alethea: Sandy 1982.

- Watson, Alexander, The Ochils – Placenames, History, Tradition, Perth & Kinross District Libraries 1995.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.