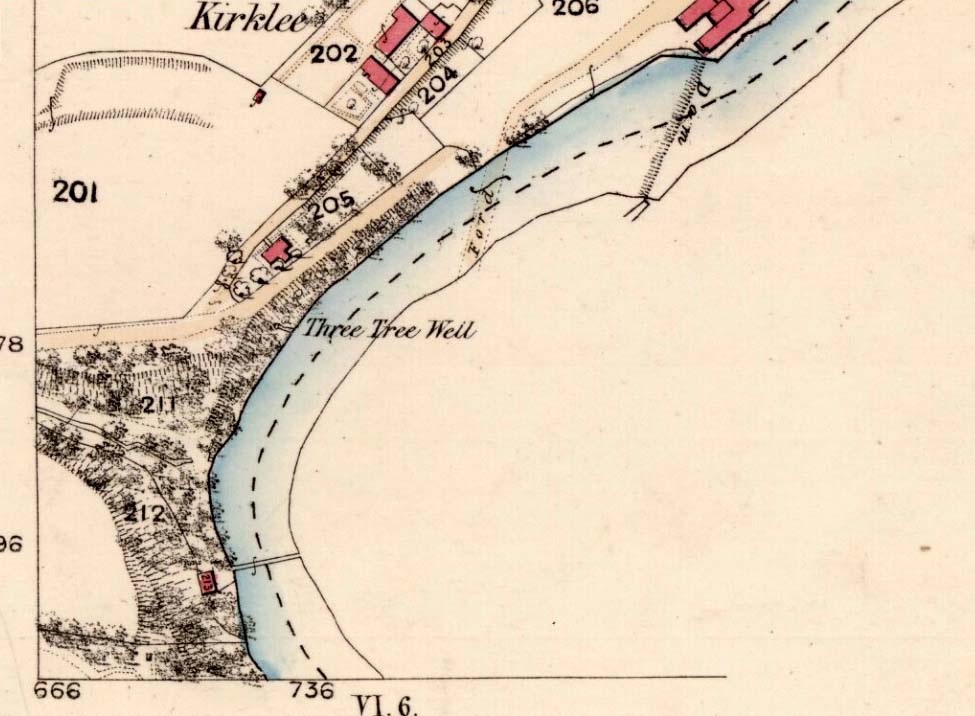

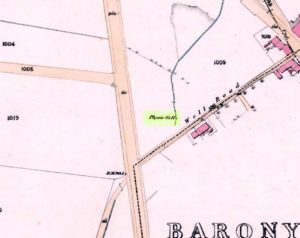

Healing Well (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NS 5805 6728

Archaeology & History

Any site named as a ‘Physic Well’ anywhere in Britain is, by definition, a spring of water renowned for its medicinal properties. Nowadays however, at this and other sites with the same name, local people aren’t even aware that such places exist. A sad state of affairs indeed… This Physic Well was once found just off Trossach Street in Maryhill—which was once called ‘Well Street’, after the medicinal spring itself—in fields just above the road. Today a small housing estate has been built on top of the site and the only sign of it ever being here appears to be marked by a birch tree in the gardens at the middle of the enclosing buildings.

The site was listed in several early 19th century municipal surveys of Glasgow, but the greater references to it seem to be from local people who described it as a place that was visited annually along the perambulation of the old Barony parish, despite it being just over the edge and into Maryhill. In an extensive footnote in Renwick’s Glasgow Memorials he gives us a fascinating insight into the gatherings at the Well, and the popular customs and social activities of the period:

“William Graham, of Lambhill, aged 69, recollected in his school days, “drinking at a well a very little to the north of the Barony glebe, which was called the Physic Well, and there was then a Royalty stone a little to the west of the glebe.” The Physic Well, perhaps all that effective drainage had left of the former loch, otherwise called ‘Plommaris Hole,’ was utilised at the periodic perambulation of marches for impressing on the memory recollection of this part of the boundary. The means taken for this end may be gathered from the evidence of John Alston, weaver, aged 54, who says that, when he was an apprentice, his master told him that it was a custom, “when the magistrates rode the marches to duck some of the last-made burgesses in the Physic Well”; and, on the same topic, James Bryce, victualler, aged 70, depones that, forty years ago, it was commonly reported in the town that at the marches-riding it was the custom “to duck the youngest town-officer in a well called the Physic Well, which is now filled up, but which was near the Barony glebe.” Janet Paterson, widow of William Paterson, labourer, aged 78, recollects of another well, called the Loanhead Well, in the Barony Glebe, from which she carried water when a young girl. ”About 57 yean ago she saw two ploughs going in the Barony Glebe on the Fast Day of the town Sacrament. In general people wrought the Physic Well Park on the town’s Fast Day, but she never saw them working on the Barony Glebe except on the occasion mentioned.” William M’Culloch, farmer, Lightbum, aged 57, says that when Mr. Hill was minister of the Barony parish, the deponent’s father was employed by him, for a good many years, to plough the Barony Glebe, and on one occasion he recollects the glebe being sown and harrowed upon a Fast Day preceding the town Sacrament. Mr. Hill told his father that the glebe was not within the town’s bounds, that the sowing and harrowing it on the Fast Day could disturb nobody, and that his father could have the sowing finished in time to go to church. Peter Ferguson, weaver, aged 5$, had resided in the neighbourhood of the Barony Glebe from his infancy. When he was a boy he heard it very frequently mentioned by old people, as a common report, that when delinquents or debtors, prosecuted before the town courts of Glasgow, were pursued by the town officers, for the purpose of being apprehended, they were in the practice of endeavouring to get across the Howgate Strand; and if they accomplished this they set the officer at defiance and pointed their fingers at them in derision, as being then without the city’s jurisdiction. Howgate Strand was a small run of water which crossed Castle Street, at the south end of the glebe, then passed through the infirmary grounds and joined the Molendinar Burn a little to the north of the High Church. Another witness, Thomas Alston, manucturer, aged 55, places the fugitives’ point of escape at the north end of the glebe. In his young days it was the practice for the town officers to apprehend boys who were playing on the streets upon the Sabbath and the Fast Days preceding town Sacraments; and he remembered well that it was a common opinion with him and his companions that they were safe from the town officers when they got beyond the Physic Well, on the Glasgowfield road, or beyond the spot marked on Mr. Fleming’s plan ‘Toll-house’, on the Kirkintilloch road, as they considered themselves to be then without the town’s jurisdiction.”

The Well was close to a series of old boundary or ‘merche’ stones, but no ancient ones seem to remain.

The medicinal potential for the water was examined in 1771 by a Dr William Irvine, who found it to be a chalybeate or iron-bearing spring, and to possess “a little muriatic acid”, giving the well both tonic and fortifying properties.

References:

- Irvine, William, Essays, Chiefly on Chemical Subjects, J. Mawman: London 1805.

- Renwick, Robert, Glasgow Memorials, James Maclehose: Glasgow 1908.

Acknowledgements: Huge thanks to Nina Harris for guiding us to the spot where this old well once existed.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian