Cursus Monument: OS Grid Reference – SU 1056 4350

Also Known as:

- Small Cursus

- Stonehenge Smaller Cursus

Archaeology & History

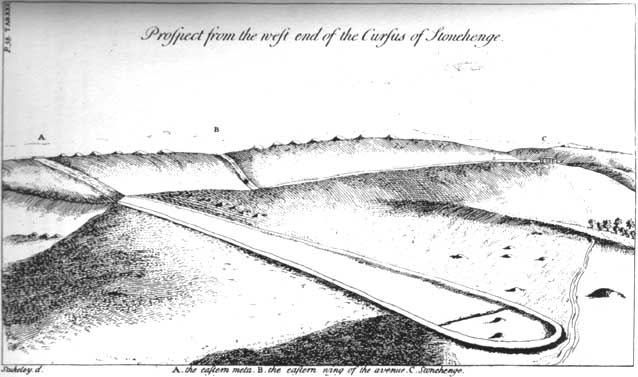

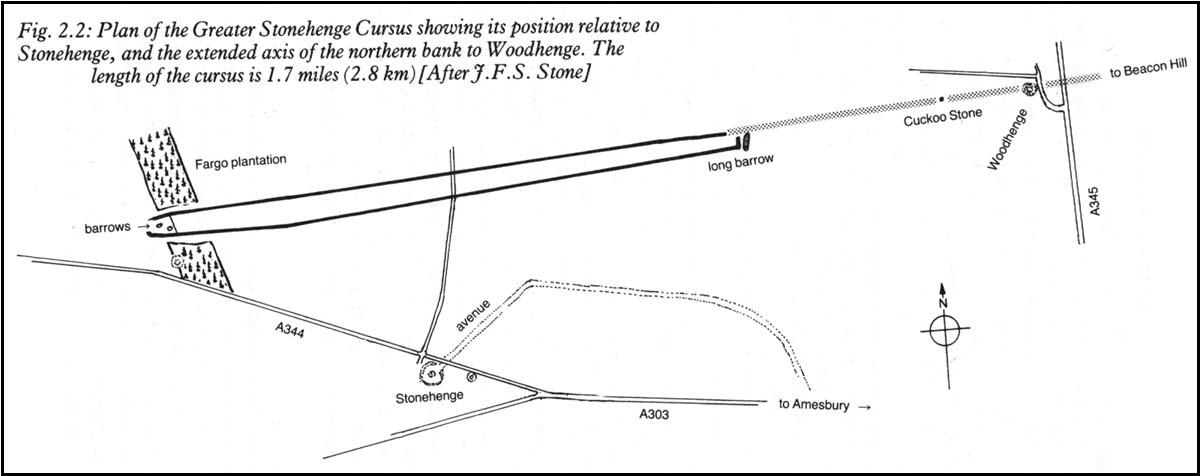

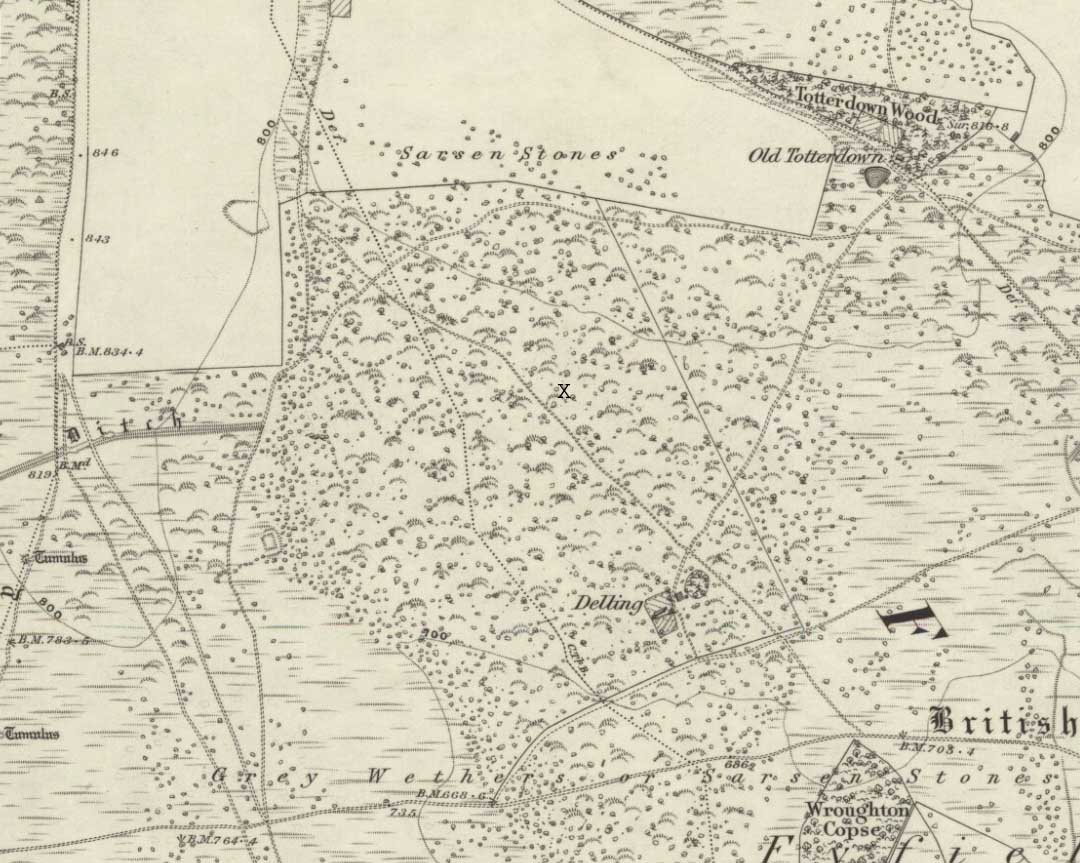

Just like its much larger companion, the Stonehenge Cursus earthwork a short distance to the south, this Lesser or Small Cursus is generally deemed by archaeologists to “speak of a clear religious or ritual aspect to this patch of downland that…reaches back generations before the first Stonehenge was built.” (Pitts 2001) The monument was aligned roughly east-west, showing possible relationships with the rising and setting of both sun and moon. (though I wouldn’t get too carried away with that misself…)

When Fergusson (1872) described this and its larger cursus companion a few hundred yards away, he thought they may have been dug to mark out lines of battle in prehistoric times, denouncing the horse-racing course hypothesis that was still in vogue at the time. His theory drew evidence from the numerous prehistoric tombs scattering this area of Salisbury Plain, but seemed more influenced by notions of prehistoric barbarism and warfare than ideas relating to a cult of the dead — which was yet to reach it heights in the archaeological minds of Victorian England. But, like other cursus monuments all over the British Isles, this one also seemed to have a distinct relationship with monuments of the dead: for at its western extremity (until being ploughed out of existence) was a large round barrow, catalogued as the “Winterbourne 35” tomb. Tim Darvill (2006) tells its wider tale:

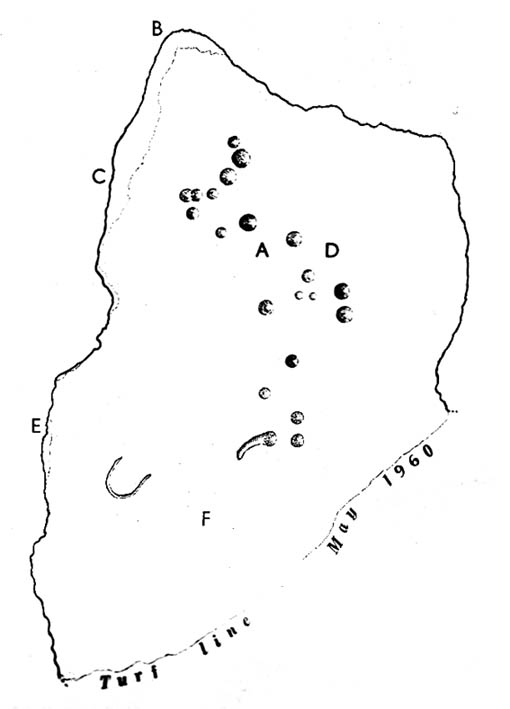

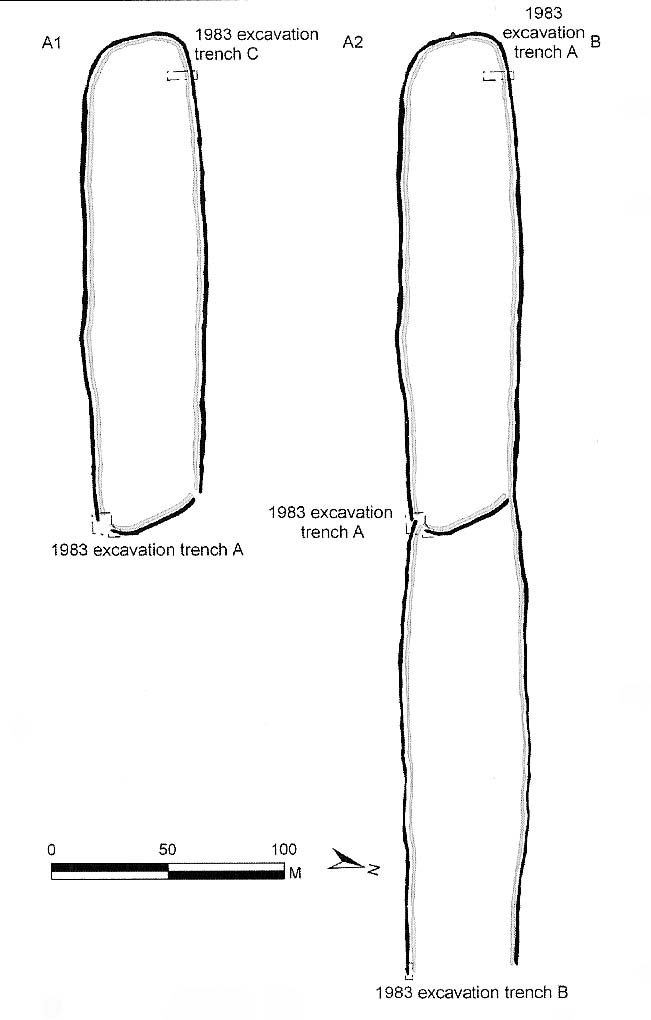

“Levelled by ploughing between 1934 and 1954, the Lesser Cursus was investigated in 1983 as part of the Stonehenge Environs Project… Three trenches were cut into different parts of this large monument, showing that there were at least two main phases to its construction. Phase 1 comprised a slightly trapezoidal enclosure 200m by 60m, whose ditch may have been recut more than once and in part at least deliberately back-filled. In Phase 2 this early enclosure was remodelled by elongating the whole structure eastwards by another 200m. This extension comprised only two parallel side ditches, making the whole thing about 400m long with a rectilinear enclosure at the west end with entrances in its northeast and southeast corners giving access into a second rectilinear space, in this case open to the east.”

The entire structure had finds dating from the periods between 3650-2900 BC; and the aerial imagery showing an oval-shaped structure near the eastern end was confirmed by geophysical surveys — though precisely what this is has yet to be ascertained.

It seems likely that this and other cursus monuments were, to a very great degree, not only related to mortuary practices but — as their development occurred at the same time as the destruction of Britain’s great forests began — to be monuments to the gods themselves. This seems very evident at a couple of cursus monuments where animal deposits were made in some of the great mounds at their terminii, where archaeologists had previously assumed— incorrectly — the mounds to have been human burial mounds. More about this in due course…

References:

- Darvill, Tim, Stonehenge: The Biography of a Landscape, Tempus: Stroud 2006.

- Devereux, Paul, The Haunted Land, Piatkus: London 2001.

- Fergusson, James, Rude Stone Monuments in all Countries, John Murray: London 1872.

- Loveday, Roy, Inscribed Across the Landscape, Tempus: Stroud 2006.

- North, John, Stonehenge, Harper-Collins: London 1997.

- Pitts, Mike, Hengeworld, Arrow: London 2001.

- Richards, Julian, The Stonehenge Environs Project, English Heritage: London 1990.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian