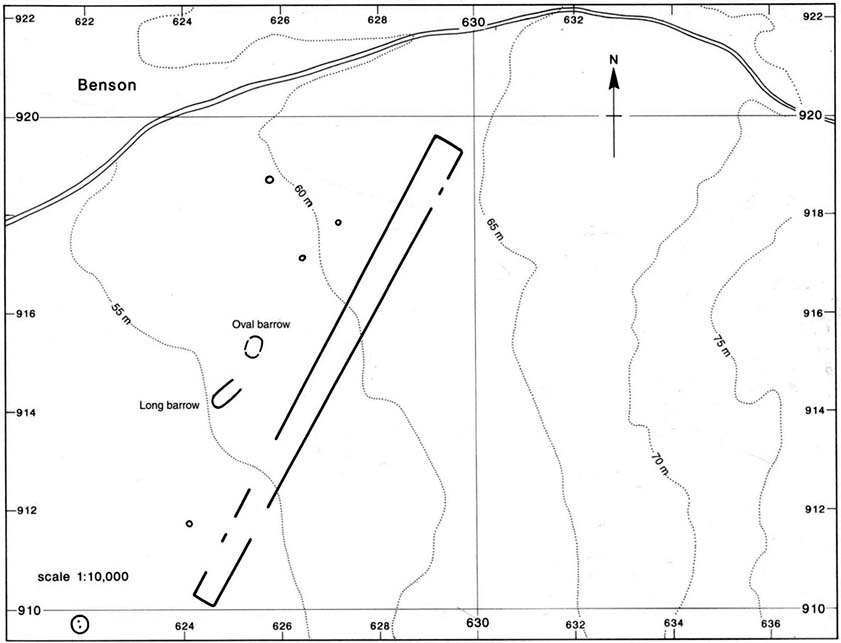

Standing Stones (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SY 6070 8701

Also Known as:

- Jefferey and Jone

Archaeology & History

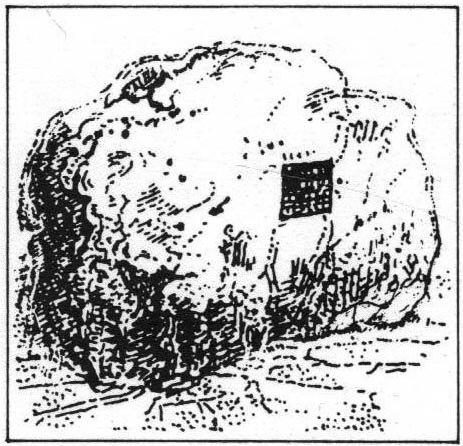

Described in early field-name listings as ‘Jefferey and Jone’, this was another group of standing stones, whose precise nature is difficult to truly discern, that met with an untimely end in the middle of the 19th century. They may have been part of a large tomb, or even a stone circle. Marked on the early Ordnance Survey map of the area as ‘Standing Stones (site of)’, they appear to have been described firstly by John Hutchins (1774) close to other megalithic remains, who told that:

“A little north of Hell Stone near Blagdon are four upright stones, near to, and equally distant from each other, about two feet high, except that one is broken off even with the ground.”

In Warne’s (1866) classic text he mentioned these petrified monoliths,

“In a small valley, on the down of Portesham Farm, there stood within these last ten years, four upright stones… By the direction of the then occupier of the farm, Mr Manfield, these stones were built into an adjoining wall.”

A few years later another account by H.C. March, which referred to Mr Warne’s description, gave another report citing information from one who was present at the destruction of the site:

“Warne says they have been built into an adjacent wall: but a man who was present at the ceremony stated that, by the spot where they once stood, a hole was made for them, and they were decently interred. The place where they are said to lie can be pointed out, as well as a wall which contains four large stones.” (Harte 1986:54)

Historian and folklorist Jeremy Harte (1986) concluded that the megaliths must obviously have been destroyed around the year 1855. However, the historical references of Jeffrey & Jone being moved into the adjacent walling appears to be verified by independent researchers who’ve found standing stones hereby.

Folklore

Very probably the remains of petrified ancestors, a curious rhyme describes a forgotten folktale of these lost standing stones relating to them as possessing spirit, or once being alive. They were thought of once as being a family who lived in the hills:

“Jefferey and Jone,

And their little dog Denty

and Edy alone.”

Sadly, I can find nothing further that might enrich the folktales that were obviously once spoken of these monoliths.

References:

- Harte, Jeremy, Cuckoo Pounds and Singing Barrows, Dorset Natural History & Archaeological Society 1986.

- Hutchins, John, The History and Antiquities of Dorset, John Bowyer & J Nichols: London 1774.

- Warne, Charles, The Celtic Tumuli of Dorset, John Russell Smith: London 1866.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian