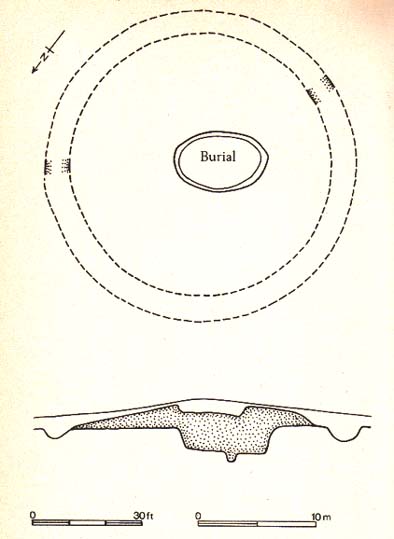

Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – TL 975 247

Fortunately for the person who lives here, this much overgrown and denuded remains of a fabled tumulus is in their garden! The mound is divided by a hedge in the back garden, up near the bend of where Fitzwalter Road meets St. Clare Road and the school field backs onto them. I’ve no idea whether the people who own the gardens are OK with you visiting the site or not. If you wanna look at it, I s’ppose the only thing to do is knock on their door and ask!

Archaeology & History

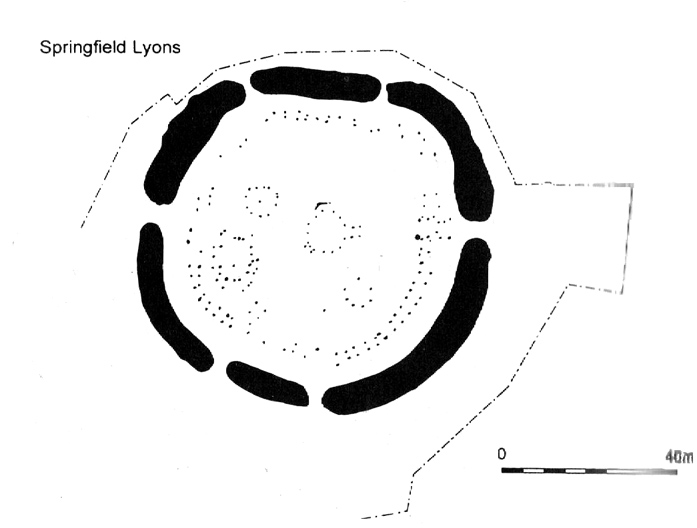

Ascribed as late Iron Age, some of the finds here are distinctly Romano-British. Indeed, excavations here by P.G. Laver in 1924 uncovered rich Belgic remains akin to the chariot burials found in East Yorkshire! (though not quite as good as them) There was a considerable collection of gold, silver and other metalwork remains here, along with considerable remains of pottery aswell. It seems there was a tradition of burials here, with some evidence dating from the Bronze Age — but the majority of remains found in the excavations were from the much later period. One account attributes the burial mound to have held the body of Cunobelin; the other, the body of Addedomaros of the Trinovante tribe.

Folklore

Quoting from an earlier source (A.H. Verrill’s Secret Treasure, 1931), in Leslie Grinsell’s (1936) fine early survey on British prehistoric tombs, he described the legend of there being hidden treasure here, saying that locally there was

“a belief that it was the burial place of a king in golden armour, with weapons and a gold table.”

But was this legend described anywhere before P.G. Laver’s excavation of the site in 1924…? It would be very intriguing if we could find this out!

References:

- Grinsell, Leslie V., Ancient Burial Mounds of England, Methuen: London 1936.

- Laver, P.G., ‘The excavation of a Tumulus at Lexden, Colchester,’ in Archaeologia journal, no.76, 1927.

Links:

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian