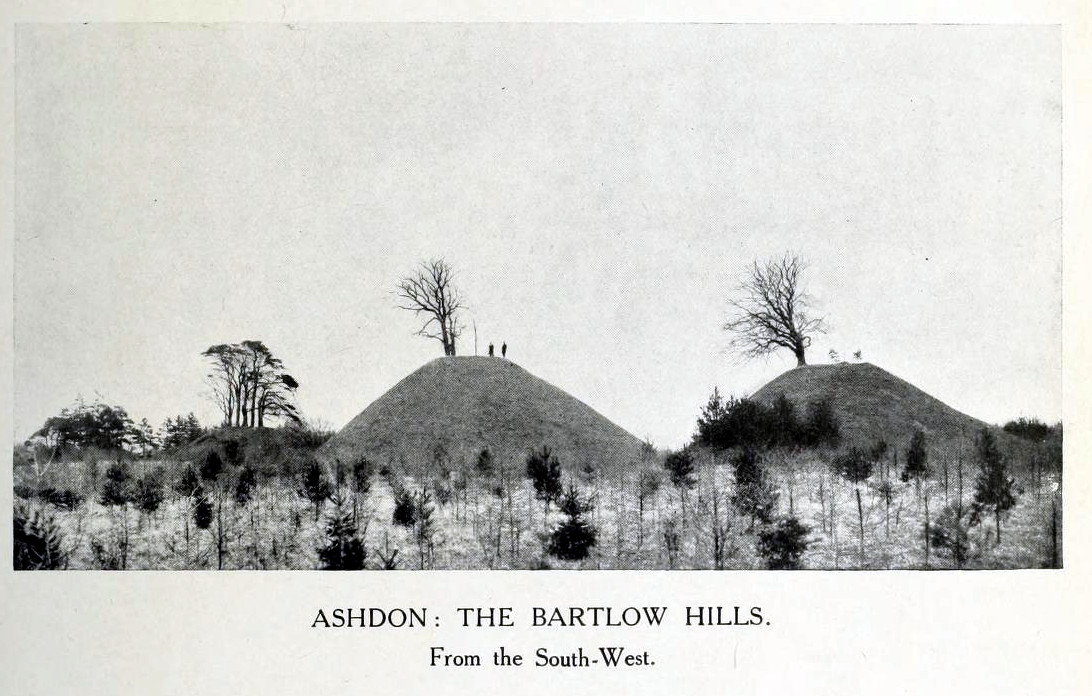

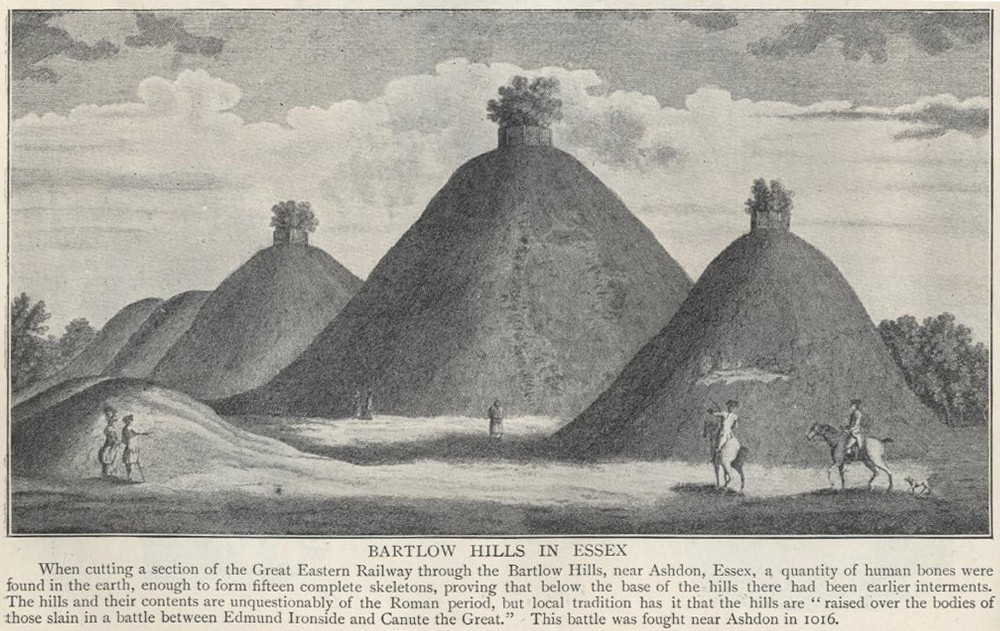

Tumulus (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – TL 5801 5874

Archaeology & History

In times of olde on this prominent tree-covered hill, a tomb of some ancient ancestor once lived. It had already been destroyed by some retards by the time the Ordnance Survey lads came here in 1885; but thankfully, memory gave its existence the note it deserved. The place had thankfully been given the once-over by some archaeologists in the middle of that century, giving us a pretty good idea as to its size and nature. Measuring some 90 feet across and fourteen feet high, this was no mere toddler!

A Mr W.T. Collings (1846) gave his Intelligence Report to the archaeological journal of the period, from which the following description is gained:

“The excavation of this tumulus in 1845 was made from east to west, commencing from the eastern side, in the direction of its centre, in which, at a depth of about three feet, there was found a cinerary urn in an inverted position, slightly tilted on one side, and surrounded by charcoal and burnt earth. It was filled with charcoal, but contained only one small fragment of bone. This vessel, which was of the simplest manufacture, moulded by the hand, and sun-baked, measured in height five inches, and its diameter at the largest part was five inches and a half. From the deep red colouring, and the general appearance of the surrounding soil, it would seem that a small hole had been first dug, charcoal and bones burnt in it, the vase placed on the fire in an inverted position, and the whole covered up. About ten feet eastward of the central deposit, on the south side of the line of excavation, and half a foot deeper, a deposit of fragments of bone was found apparently calcined, but with little charcoal or burnt earth, forming a layer not more than three inches thick, and two feet in circumference. There were several pieces of the skull, a portion of the alveolar process, inclosing a tooth, apparently that of a young person, pieces of the femur and clavicle, and other fragments. A little to the north of this spot there appeared a mass of charcoal and burnt earth, containing nothing of interest. After digging five or six feet deeper, operations were discontinued; and on the next day shafts were excavated from the centre, so as completely to examine every part, without any further discovery, and in every direction charcoal was found mingled with the heap, not in patches, but in fragments.”

Collings reported the existence of another burial mound a short distance to the south. It was one of at least five such tumuli in the immediate locale, all of which have been destroyed by retards in the area.

References:

- Collings, W.T., “Archaeological Intelligence,” in Archaeological Journal, volume 3, 1846.

- Hore, J.P., The History of Newmarket – volume 1, A.H. Baily: London 1886.

- Royal Commission Ancient Historical Monuments, Inventory of Historical Monuments in the County of Cambridgeshire – Volume 2: North-East Cambridgeshire, HMSO: London 1972.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.