Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – NS 7253 9906

Also Known as:

- Canmore ID 46065

- Old Farm

Getting Here

Caravan Park burial mound

Along the A84 Stirling-Doune road, watch out for the minor Cuthill Brae road to the caravan park. Go up and into Blair Drummond caravan park (ignore the old grumpy southern-type fella who tells you “this is private”), right into and through the walled area where the caravans are situated. Out the other side is a children’s playground— and the very large mound to your left with a tree on top (and a children’s slide built on it) is the burial mound in question.

Archaeology & History

Tumulus from the southeast

This comes as something of a surprise when you first set eyes on it. It’s big! (bigger than I expected anyway!) Seemingly on its own, rising from the level ground and surrounded by cultivated land, there were probably others of its kin close by, but the closest that we know about is 1.5km to the east; although the standing stone of Boreland Hill a few hundred yards west might have had some relevance….

This tumulus may be the one noted by Charles Roger (1853) in his visit to the area. He spoke of the now denuded burial mound to the east (in the Safari Park), but also told that,

“Within the park are two other tumuli, one situated in the garden, of a conical form and measuring 92 yards in circumference and about 15 yards in height…”

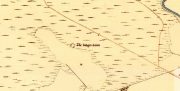

Blair Drummund tumulus on 1866 OS-map

This mound is more 15 feet in height than yards, but the other measurement is close—and it does seem to be in the right area.

There is much greater certainty in J.G. Callander’s (1929) account. He was fortunate in being part of the excavations undertaken here by Sir Kay and Lady Muir in 1927-28 and gave a damn good account of what went on:

“The mound is not quite circular, as it measures about 75 feet in diameter from north to south and about 65 feet from east to west, its height being about 15 feet. Before the excavations were started it seemed as if the monument consisted entirely of earth, but before the examination was completed it was found that it contained a small cairn of stones, heaped over a grave formed of large slabs arid boulders which undoubtedly was the primary interment.

“Commencing at the south-south-eastern edge of the mound, a trench driven in towards the centre, revealed the presence of a short cist which had apparently been disturbed at some previous time. A large block of stone formed the northern end and a large slab the east side. A smaller slab lay at the south end and another on the west side, but as the latter was too short to fill the space, a larger slab lay obliquely between it and the large stone at the north end. There was no appearance of a cover stone. The length of this grave was 3 feet 3inches, its breadth 3 feet, and its depth 2 feet 3 inches. The longer axis lay practically north and south. No traces of human remains or relics of any sort were found here. This was evidently a secondary burial sunk into the mound as far as the original surface of the ground, and covered with about 4 feet of soil at the centre.

“As the trees interfered with further excavations at this part, another trench was cut in from the northern arc as far as the centre of the mound, where an undisturbed cist, formed of large rough slabs and a cover stone, was encountered. Although this grave was considerably larger in length, breadth and depth than any of the numerous short cists that I have examined, I think it should be classed with them rather than with the large cist-like chambers sometimes found in long cairns. It was formed of two side and two end slabs. The sides were roughly parallel, but the slab at the southern end was placed obliquely so that the length of the grave was 4 feet 6 inches on the east side and 4 feet on the west side. The general breadth was 3 feet at the floor, and the depth 4 feet. Both side slabs converged towards the top. As the slabs on the east side and at the ends were not so high as that on the west, the spaces between them and the cover stone were carefully built up with smaller stones. A slight vacancy between the slabs at the south-east corner was filled in a similar fashion. A small cairn of clean stones without a mixture of soil had been heaped up over the cist, covering the lid to a depth of about 9 inches: the diameter of the cairn at the base was not ascertained. The depth of earth above the summit of the cairn was about 8 feet. But for a layer of a few inches of earth on the floor the cist was empty. Nothing was found except some small unburnt fragments of human bone, very much decayed, and a few teeth. Some small fragments of charred wood were found in making the trench and in the grave, but whether it was charred by natural carbonisation or by burning was not determined.

“In making the trench just before the grave was reached, but at a higher level, a small portion of the cutting edge of a stone axe was found. It had no evident connection with the cist, and may have happened to be lying about amongst the soil that was piled up over the grave.

“As there remained a space on the top of the mound which could be excavated without destroying any of the trees, it was examined. About 1 foot under the surface a cinerary urn was found in an inverted position. The base had been crushed in, and the wall was full of cracks into which tree roots had penetrated. On taking it out the vessel was found to have originally been about half-filled with cremated human bones. These after examination were reinterred in the mound. No other relics were found in the urn.

“The vessel, which is formed of buff-coloured clay with a tinge of red in places, is a cinerary urn of the cordoned variety belonging to the Bronze Age. It is encircled at the widest part, about 3½ inches below the lip, by a raised moulding or cordon, and about 3 inches lower down by another. The greater part of the vessel was recovered, but as the basal portion was completely crushed, it is impossible to ascertain the height of the vessel or the width of the base when complete. It measures 10¾ inches in external diameter at the mouth and 11⅞ inches at the widest part: what remains of the wall is 13 inches in height. The rim, which is unusually thin for a vessel of this class, is only ⅜-inch in thickness, and it is bevelled downwards towards the interior. The space between the upper cordon and the rim is the only part which is decorated, and here there is a row of large triangles, alternately plain and filled, with a reticulated design, bordered above and below with a single marginal line, all formed by pressing a twisted cord on the clay before it was fired.”

Protected tumulus, damaged by slide

The burial mound is still in a reasonably good state of preservation… on the whole… There is however, a slightly worrying note: this tumulus is a protected scheduled monument but despite this it has, as of late, been quite deliberately built upon. When Penny Sinclair and I visited the nearby Christ’s Well recently (out of season), an unhelpful grumpy man working or living there told us we were “not allowed on the site – it’s private.” We thought he was joking and I laughed that, “This is Scotland!” He repeated his words. A week later, Paul Hornby and I revisited the Christ’s Well and then took to see this large burial mound – only to find that a children’s play area had been built right up to, and upon, the northwestern part of the monument. This is in contravention of legal regulations to build upon Scheduled Monuments, as:

“The area to be scheduled encompasses the mound and an area around it in which traces of associated activity may be expected to survive.”

This has been violated.

If you like your prehistoric burial mounds, this is well worth having a look at.

References:

-

- Roger, Charles, A Week at Bridge of Allan, Adam & Charles: Edinburgh 1853.

-

Royal Commission on the Ancient & Historical Monuments of Scotland, Archaeological Sites and Monuments of Stirling District, Central Region, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 1979.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.