Ring Cairn: OS Grid Reference – SE 07496 38675

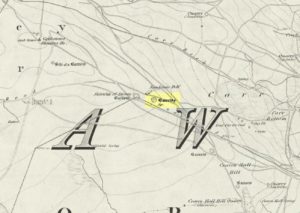

From Harden, go up Moor Edge High Side (terraced row) till you reach the top. Follow the path thru’ the woods on the left side of the stream till you bend back on yourself and go uphill till you reach the moor edge. Keep walking for about 500 yards and keep an eye out to your immediate left. The other route is from the Guide Inn pub: cross the road and go up the dirt-track on the moor-edge till you reach a crossing of the tracks where a footpath takes you straight onto the moor (south). Walk on here, heading to the highest point where the path eventually drops down the slope, SE. As you drop down, watch out for the birch tree, cos the circle’s to be found shortly after that, on your right, hidden in the heather!

Archaeology & History

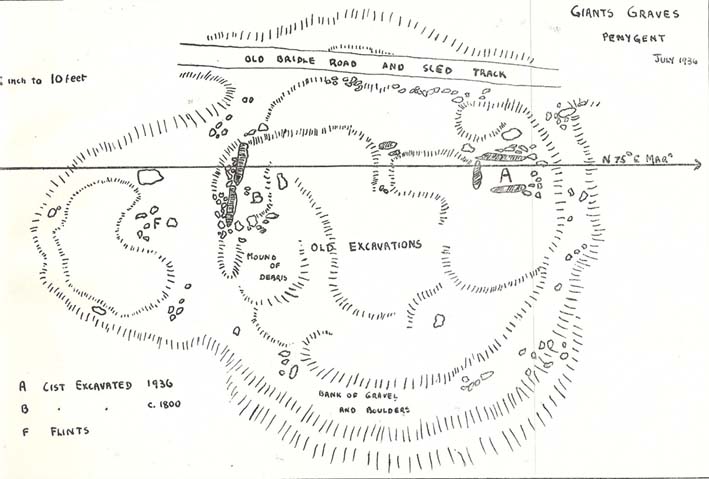

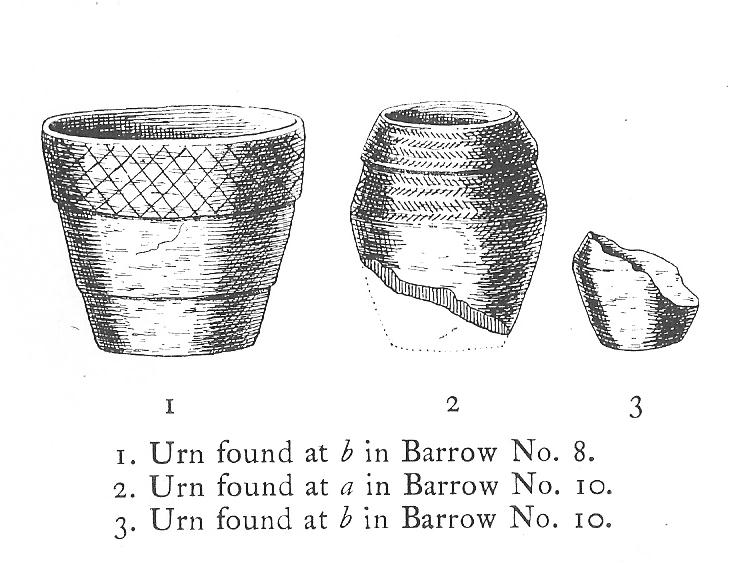

This aint a bad little site hidden away on the small remains of Harden Moor, but is more of a ‘ring cairn’ than an authentic stone circle (a designation given it by previous archaeologists). An early description of it was by Bradford historian Butler Wood (1905), who also mentioned there being the remains of around 20 small burials nearby. When the great Sidney Jackson (1956; 1959) and his team of devoted Bradford amateurs got round to excavating here, he found “four or five Bronze Age urns” associated with the circle. His measurements of the site found it to be 24 feet across, and although the stones are buried into the peat with none of them reaching higher than 3 feet tall, it’s a quietly impressive little monument this one. About 20 upright stones make up the main part of the ring.

I’ve visited the place often over the last year or so since a section of the heather has been burnt away on the southern edges of the circle. This has made visible a very distinct surrounding raised embankment of packing stones about a yard wide and nearly two-feet high, particularly on the southern and eastern sides of the circle, giving the site a notable similarity in appearance and structure to the Roms Law circle (or Grubstones Ring) on Ilkley Moor a few miles to the north.

There is also the possibility that this ring of stones was the site described by local historian William Keighley (1858) in his brief outline of the antiquities of the region, where he wrote:

“On Harden Moor, about two miles south of Keighley, we meet with an interesting plot of ground where was to be seen in the early days of many aged persons yet living, a cairn or ‘skirt of stones,’* which appears to have given name to the place, now designated Cat or Scat-stones. This was no doubt the grave of some noted but long-forgotten warrior.

* The Cairn was called Skirtstones by the country people in allusion to the custom of carrying a stone in the skirt to add to the Cairn.”

However, a site called the ‘Cat stones’ is to be found on the nearby hill about 500 yards southeast – and this mention of a cairn could be the same one which a Mr Peter Craik (1907) of Keighley mentioned in his brief survey of the said Catstones Ring at the turn of the 20th century. We just can’t be sure at the moment. There are still a number of lost sites, inaccuracies and questions relating to the prehistoric archaeology of Harden Moor (as the case of the megalithic Harden Moor Stone Row illustrates).

The general lack of an accurate archaeological survey of this region is best exemplified by the archaeologist J.J. Keighley’s (1981) remark relating specifically to the Harden Moor Circle, when he erroneously told that, “there are now no remains of the stone circle on this site” — oh wot an indicator that he spent too much time with paperwork! For, as we can see, albeit hidden somewhat by an excessive growth of heather, the ring is in quite good condition.

It would be good to have a more up-to-date set of excavations and investigations here. In the event that much of the heather covering this small moorland is burnt back, more accurate evaluations could be forthcoming. But until then…..

References:

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Craik, Peter, “Catstones Ring,” in C.F. Forshaw’s Yorkshire Notes & Queries, volume 3 (H.C. Derwent: Bradford 1907).

- Faull, M.L & Moorhouse, S.A. (eds.), West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey to AD 1500 – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Jackson, Sidney, “Harden Moor Circle,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 1:18, June 1956.

- Jackson, Sidney, “Harden Circle Found,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, 2:1, July 1956.

- Jackson, Sidney, “Bronze Age Urn found on Harden Moor,” in Cartwright Hall Archaeology Group Bulletin, no.7, 1959.

- Keighley, J.J., “The Prehistoric Period,” in Faull & Moorhouse, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Keighley, William, Keighley Past and Present, Arthur Hall: London 1858.

- Wood, Butler, ‘Prehistoric Antiquities of the Bradford District,’ in Bradford Antiquary, volume 2, 1905.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian