Cup-Marked Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 13858 45562

Also Known as:

- Carving no.190 (Hedges)

- Carving no.367 (Boughey & Vickerman)

Getting Here

The easiest way to find this is to take the same directions to reach the Woofa Bank settlement. Get your compass out and make sure that you’re at the northern edge of the settlement walling. From here, walk about 60 yards northwest and keep your eyes peeled for a rock about 2 feet high, curved and elongated with its top surface above the heather. You’ll find it.

Archaeology & History

The name I’ve given to this stone is a conjectural one based entirely on comparative petroglyph designs elsewhere in the world. Or to put it more simply: elsewhere in the world we find examples of prehistoric rock art showing animal tracks and rituals relating to hunting animals, and in the design of this petroglyph on Ilkley Moor I wondered if we might be looking at something similar. Internationally respected anthropologists, archaeologists, geologists and rock art specialists such as Lawrence Loendorf (2008), Polly Schaafsma (1980), Dennis Slifer (1998) and many others show examples of animal tracks in the US and Mexico (examples exist throughout the world), and it’s not unlikely that some of the petroglyphs in the UK represent such things. But, like I say, this particular carving may have nowt to do with such a thing and the idea is entirely conjectural on my part and is probably way off the mark.

Located less than 60 yards (54m) northwest of the impressive Woof Bank enclosure, it’s possible that the first literary note of this was by Stuart Feather (1968) when he made note of five cup-and-ring marked rocks (which) have been revealed by erosion in 1968,” telling us that some of the motifs on the rocks included cups with and without rings, channels and eye-shaped marks (occuli)— the latter of which may relate to this stone.

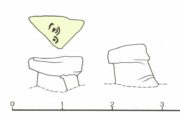

A more definite description of the stone was made in John Hedges (1986) survey where he described it in that usual simplistic form, telling us: “Long rock, its surface on two levels, sloping N to S in heather. Two large oval cups and one cup at N end. One clear cup at S end.”

It is these two elongated cups that have the distinct appearance of deer tracks. (another animal with a similar footprint is the goat) The cup-mark in front of them and the one at the back of the rock may be something relative to the animal. But more important than this is to recognise that, in lots of cultures, animal tracks are represented in some petroglyphs. That’s more important to think about when you look at British rock art, than the improbability of this design being such a thing…

References:

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Wakefield 2003.

- Feather, Stuart, “West Yorkshire Archaeological Register – Ilkley (WR) Green Crag Slack,” in Yorkshire Archaeology Journal, volume 42, 1968.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombalds Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Loendorf, Lawrence L., Thunder and Herds – Rock Art of the High Plains, Left Coast: Walnut Creek 2008.

- Schaafsma, Polly, Indian Rock Art of the Southwest, University of New Mexico Press 1980.

- Slifer, Dennis, Signs of Life – Rock Art of the Upper Rio Grande, Ancient City: New Mexico 1998.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian