Tumulus: OS Grid Reference – SD 90693 65374

Also Known as:

- New Close tumulus

From Malham village go over the lovely old bridge and follow the road up and round, keeping to the left (not up the Gordale Lane) where the junction appears a few hundred yards along. Follow this steep and winding road all the way to the top for a couple of miles until you hit a junction seemingly in the middle of nowhere. Park up somewhere to the left and notice the hillock which you’ve just passed on your right (east) with a bittova flat top to it. Cross the stile and go up to it!

Archaeology & History

Although somewhat overgrown thanks to the persistence of Nature, this good-sized burial mound on top of this, one of many small hills in and around the moors hereby, is a fine specimen to behold and a fine place to sit and drink in the view. Although not quite having the grandeur of the Great Close Hill tomb a mile to the north, the countryside hereby is still impressive and was of obvious importance in the mythic landscape of our Bronze Age ancestors. If you think otherwise, there’s obviously summat wrong with you.

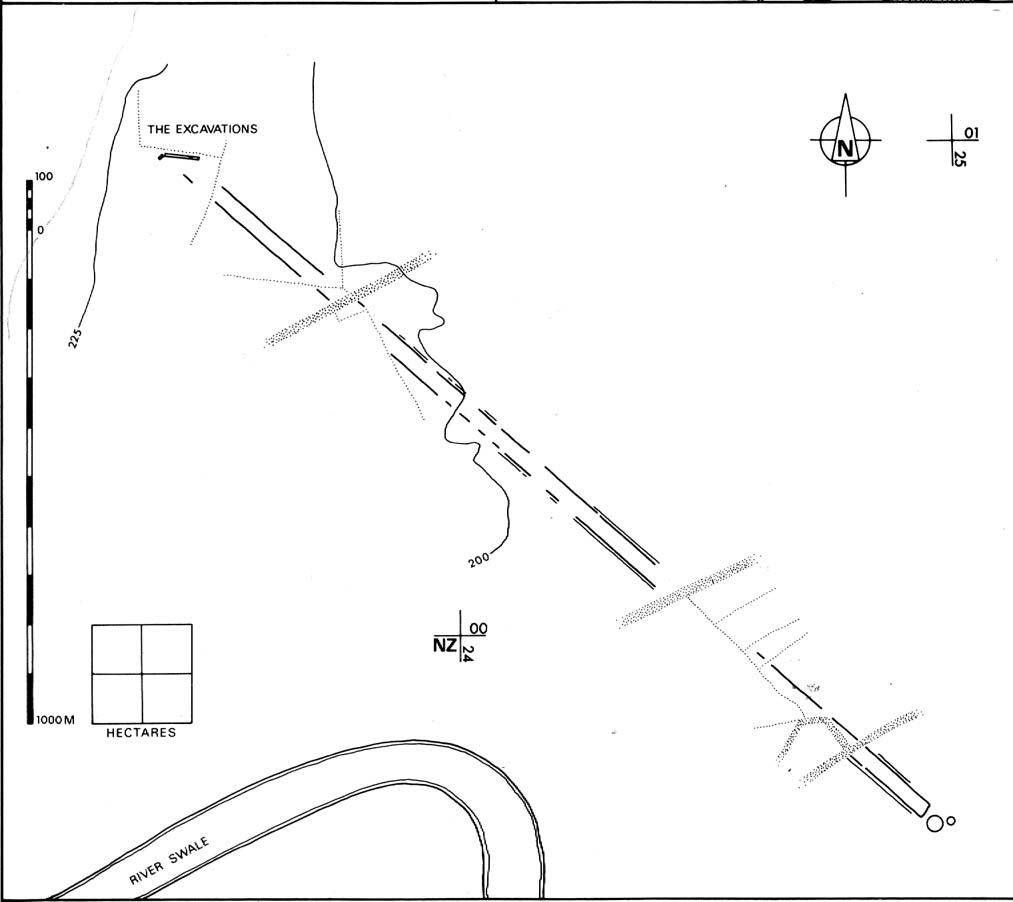

Although we can only see the remains of one singular round tomb today, at least two other tumuli were once in evidence in this large open field but they were dug out many years back. There were probably even more of them, but any trace has long since gone. Thankfully this one was given the attention of decent archaeologists some fifty years back, when Arthur Raistrick (1962) and his mates got stuck into the place. His initial account of the place told us how it was,

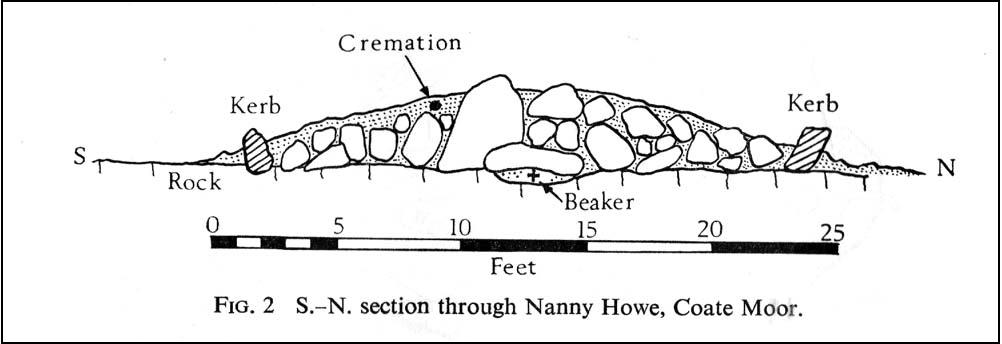

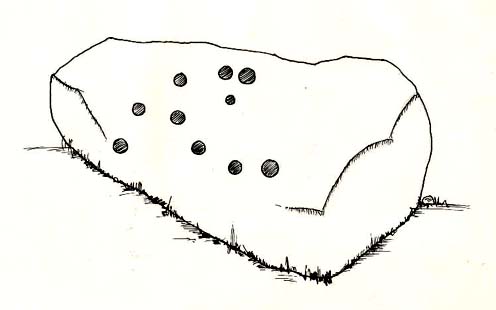

“…surrounded by a shallow ditch and bank enclosing a low mound 66 feet diameter, rising about 4 feet above the ditch bottoms. In the original surface of the hill top there had been dug two holes, circular and partly impinging on one another, both 3ft 6in deep. In the northwesterly one of these a skeleton had been carefully placed in a sitting position, with knees drawn well up, and was facing the second hole which is to the southeast. This hole was almost filled by a carefully built cairn of limestone boulders, but nothing was found either in or beneath it. No artifact of any kind was found with the skeleton. Both holes had been filled in with fine sandy and gravelly loam to the natural ground level and then covered with a low mound, 15 feet in diameter and 1 foot high, of coarser gravel and small boulders. The second mound, 66 feet diameter, of limestone rubble and boulder clay and 3 feet high above ground level, was put over this and provided with a kerb of large limestone boulders buried in the toe of the mound. A shallow ditch was then dug and its spoil thrown outwards to form a shallow bank.

“In the surface of the large mound there were not less than 13 secondary burials of early Iron Age, each in a small saucer-shaped depression filled in with gravelly loam. These burials are extremely fragmentary and are more like token burials than complete ones. In three of them, beads were found, one of jet, one of blue glass and one of carved limonite. In a burial nearly over the central older burial, a skeleton was arranged with a bone (musical) pipe between the knees, where also there were several small bones of hand and wrist and part of an iron knife. The (musical) pipe was made from the tibia of a sheep, perforated with three finger holes, with a well-shaped speaking lip and mouthpiece. The pipe was playable… A full account of this unique instrument has been published elsewhere… In two of the burials there were recognizable fragments of iron knives, and in two others pieces of iron of unrecognized use, all in positions which could have been under the knee of a more primitive skeleton. By analogy and style the primary burial has been assigned to the Early Bronze Age, and the Iron Age burials to the period first century BC to the first century AD.”

It would be intriguing to ascertain how many people from this period were playing flute-like instruments such as the one found here, and whether (as with other musical instruments in all other tribal cultures on Earth) magickal virtues were assigned to it, or the music it liberated. Certainly in a great number of places around this very area where this instrument was found, many natural sites still abound with the hugely underrated virtue of silence; and upon the still air amidst which music would be cast, the echoes or else faint sense of such sound would evoke a marvel — curious or dreamt — to those upon who it fell. If you think otherwise, there’s definitely summat wrong with y’!

References:

- Raistrick, Arthur & Holmes, Paul F., Archaeology of Malham Moor, Headley Bros: London 1961.

Links:

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian