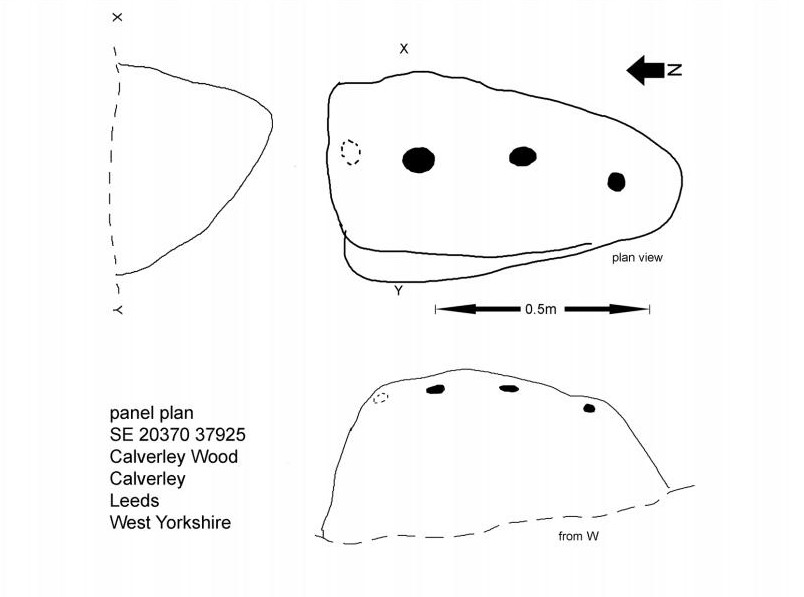

Sacred Well: OS Grid Reference – SD 36711 47562

The 6″ OS map of 1913 has a ‘Fairy Well’ marked on the northern edge of Preesall Hill. Travelling north through the village on the B5377, the Hill is to your right. Immediately past it is a stile, cross over this and go straight on with the hill to your right. The approximate site of the fairy well is now marked by a boggy area at the foot of the hill.

Archaeology & History

Almost a footnote in Reverend William Thornber’s 1852 paper on the Britons, Saxons and Danes in the Foreland of the Fylde, here is how this site is described by him in the quaint (to our eyes) language of the mid-nineteenth century:

“…the hill of Presal, (the ‘Pressonde’ of Domesday), with its well all but deified; and although the votaries, like those in the pool of Laconia, may not have cast into it cakes of bread-corn to Juno,* yet a bush was named ‘Beggar’s bush,’ from the circumstances of the offerings of rags and clouts being affixed to it, over which a prayer was said; for Bishop Hale ridicules a superstitious prayer for the blessing of clouts for the cure of diseases.”

In addition, the following reference was found on-line:

“…If the travellers had lingered, however, they would observe the inhabitants placing half eggshells on the edge of the Fairy Well at the foot of Preesall Hill; a practice of the local school children even at the beginning of the 20th century. Recording some of the traditions of the country areas of 19th century Wales, Sir John Rhys in his “Celtic Folklore”, mentioned how half eggshells were left out for the fairy folk to use as cooking pots in which to prepare food and brew beer for the reapers at harvest time.”¶

The Beggar’s Bush is long gone, but the red colour of the deposits in the adjoining ditches would indicate a chalybeate (iron-bearing) spring rather than a well, and the northern slope of the hill seems to have become an unofficial children’s play area. Curiously, at the top of the hill, next to the playground of the Fleetwood’s Charity School, there is a modern ‘beggar’s bush’, festooned with white and yellow plastic strips, in a small nature trail area…

- * quoted from Borlase, in his Natural History of Cornwall (1758): “…In Laconia they cast into a pool, sacred to Juno, cakes of bread-corn; if they sunk, good was portended; if they swam, something dreadful was to ensue.”

- ¶ http://www.lancastrians4ever.homecall.co.uk/lancastrians4ever/precha1.htm – Believed to be an online digest of out of print Preesall history publications by Stan Jones

References:

- Thornber, William, ‘Traces of the Britons, Saxons and Danes in the Foreland of the Fylde,’ in Proceedings and Papers of the Historic Society of Lancashire and Cheshire, Liverpool 1852.

Acknowledgements: – My thanks to the staff of the Local Studies Department, Borough of Blackpool Library Services for their assistance

© Paul T. Hornby, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.