Holy Well: OS Grid Reference – SK 981 897

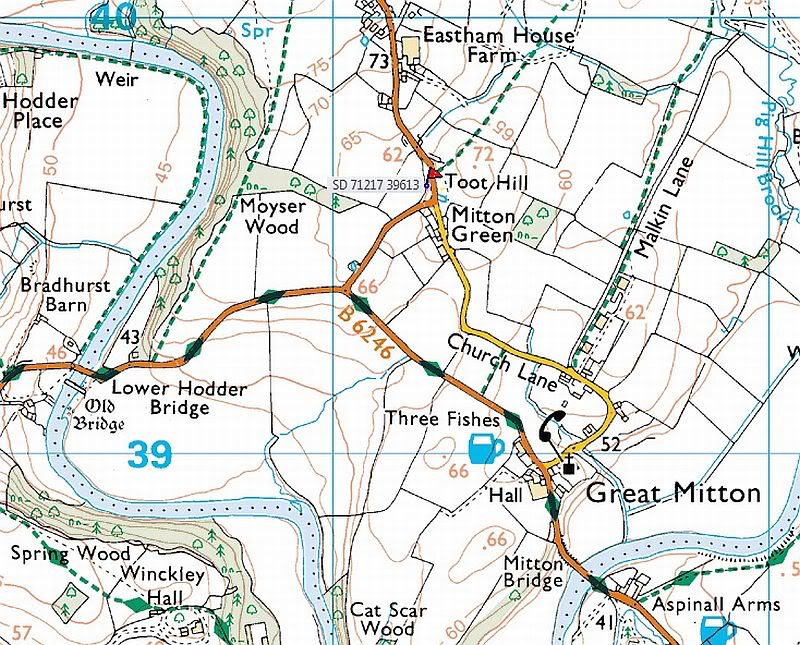

Leave Glentham on the way to Caenby Corner. You pass a footpath marked on the right-hand side (it goes to Highfield farm). The road makes a bend to the right and then before a slighter turn to the left, just before this last bend there is a little lane to the right. Park safely here and then there is copse. You will need to scramble down there and follow the small stream to its source. It runs almost just under the road.

Archaeology & History

Many wells have associations with seasonal customs, but perhaps one of the most unusual traditions is that found in the Glentham Parish in Lincolnshire. Here can be found the Newell or Newell’s Well which had associated with it a rather unique custom: the ceremony of ‘Washing Molly Grime’ The tradition appears to have become confused over the centuries. A full account is recorded by a H. Winn in Notes and Queries (1888-9):

“The church of Glentham was originally dedicated to Our Lady of Sorrows, a circumstance obviously alluded to by a sculpture in stone of the Virgin supporting the dead Christ in her arms, still to be seen over the porch entrance and placed there by some early representative of the Tourneys of Caenby, who had a mortuary chapel on the north side of Glentham church. The washing of the effigy of the dead Christ every Good Friday, and strewing of his bier with spring flowers previous to a mock entombment, was a special observance here. It was allowed to be done by virgins only, as many desired to take part in the ceremony being permitted to do so in mourning garb. The water for washing the image was carried in procession from Neu-well adjacent. A rent was charged of seven shillings a year was left upon some land at Glentham for the support of this custom, and was last paid by W. Thorpe, the owner, to seven old maids for the performance of washing the effigy each Good Friday. The custom being known as Molly Grime’s washing led to an erroneous idea that the rent charge was instituted by a spinster of that name, but ‘Molly Grime’ is clearly a corruption of the ‘Malgraen’ i.e. Holy Image washing, of an ancient local dialect. About 1832 the land was sold without any reservation of the rent charge.”

The origin for the wells name is also confused. Rudkin (1936) notes:

“They reckon it’s called Newell’s well on account of a man named Newell as left money to seven poor widow women..”

However, it is more likely to be simply new well, perhaps deriving its name from ‘eau’, a common word in the county.

When and why the tradition switched from washing the holy image to that supposedly of the Tourney (Lady Anne Tourney a local 14th century land owner) is unclear, but it is possible that the change occurred at the Reformation and that perhaps the money was given to wash both holy image and that of the benefactor and post Reformation only the benefactor washing survived. There is a similar tradition called the ‘Dusters’ in Duffield. The name of the activity clearly survived as Rudkin that:

“ they’d wash a stone coffin-top as in the Church; this ‘ere coffin-top is in the form of a women. ‘Molly Grime’ they calls it.”

The tradition even appears to have earned some note nationwide, for a nursery rhyme about the custom is known:

| Seven old maids, | Seven old maids, |

| once upon a time, | Got when they came |

| Came of Good Friday, | Seven new shillings |

| To wash Molly Grime, | In Charity’s name, |

| The water for washing, | God bless the water |

| Was fetched from Newell, | God bless the rhyme |

| And who Molly was I never heard tell. | And God bless the old maids that washed Molly Grime |

Sadly the selling of the land appeared to killed off the tradition, except that between 2004 and 2007 a special Father’s Day race for women was established. This involved filling a balloon with water from Newell’s spring and the subsequent attempt for getting it back to the village without bursting it. In essence it remembered the tradition, but sadly it too appears to have fallen into abeyance.

Folklore

Another tradition in the village was that if one drank its waters one was said never to leave the village. A correspondent of Sutton (1997) states:

“An old boy told me about the ‘healing well of Glentham. It was named after a saint but I can’t remember the name he used. Some folk call it Newell’s well. Many people came to take the healing waters and in the spring of the year, the Church held an annual service for ‘good water for the rest of the year’, the service marked a new year of the waters. The well was dressed in a traditional way using clay and flower petals to make some kind of picture, usually a saint. I’m told it look very impressive”

This is presumably before the site was enveloped in scrub as it is now. The report is interesting for a number of reasons; firstly because the correspondent refers to the waters as healing, secondly that it was dedicated to a saint and thirdly the account of well dressing more reminiscent of Derbyshire, and as far as I am aware it is only such example, as well dressing at Welton and Louth appeared to be more garland related. None of these observations have been made elsewhere which either casts doubt in the correspondent or more likely the patchy nature of well traditions in the county.

Despite the loss of the custom, the well still survives, the water clear and flowing arises beneath a stone built chamber of seven courses of stonework with a small square outlet through which the water flows. However, according to recent reports boring in the vicinity has resulted in the water being drained away but I have been unable to ascertain this.

(Essay from the book by R.B. Parish – Holy Wells and healing springs of Lincolnshire)

References:

- Parish, R.B., Holy Wells and healing springs of Lincolnshire

- Reynolds, Jeff, Glentham Parish Council – Personal Comm.

- Rudkin, E.H., (1936) Lincolnshire Folklore

- Sutton, M., (1996) A Lincolnshire Calendar

- Winn, H (1888-9) in Notes and Queries

Links:

Copyright © Pixyled Publications

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.

Perhaps what makes this well one of the most evocative and interesting is the fact that it arises in an oval grove of yew trees. Some folklorists and New age Antiquarians have seen this as being evidence of some pagan origin of the well and although it is interesting that the site is unconverted to the Christian faith. However, one must be careful. Firstly the trees do not look that old and secondly the presence of a nearby Warden’s Tower, a folly, suggests that this is perhaps a 18th century piece of antiquarianism. I have been unable to find much more of its history.