Holy Well: OS Grid-Reference – NZ 31987 64158

Getting Here

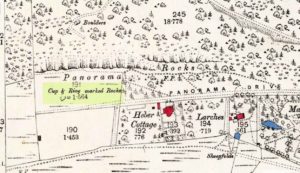

Bede’s Well on 1898 map

Gone down Adair Way and drive down as far as you can. Park and find the path back into the path this leads to the natural amphitheater down steps where the well is.

Archaeology & History

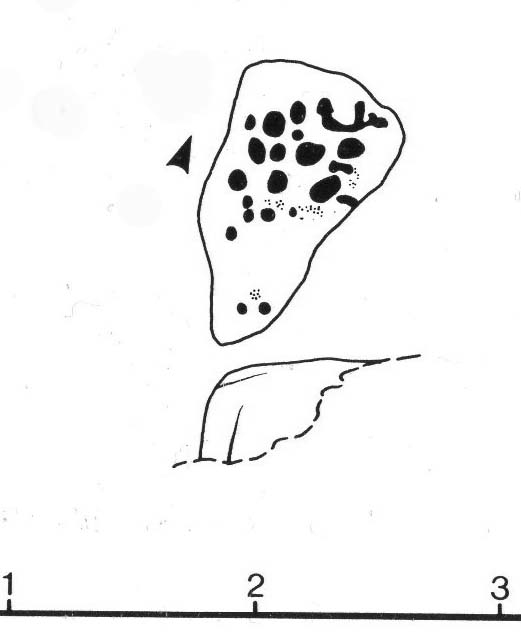

Surrounded by worn paving slabs in a small amphitheatre. It is reached by steps and surrounded by trees. The well is very dry, with broken stone work. Nearly lost under Victorian industrial growth, local people in the early 1900s became concerned with its plight and money was raised via an appeal in the Jarrow Guardian. Although some money was forthcoming, nothing appears to have happened until 1932 when it was enclosed in a railed enclosure with its name carved into the stone work either side of a gate way. When Palmer’s shipyard slag heap was consolidated sadly spring was diverted leaving the well dry.

St Bede has a long association with Jarrow but whether he knew of this well is unproved. The legend locally says that when living at St. Paul’s Monastery he would send the monks out to collect water from this well. However, it has been questioned why? Especially as the well is some distance away, a well was found enclosed in the site and in fact the river nearby would have been clean enough to drink. It is possible that the site derives its name from the Anglo-Saxon word baed meaning bathing place and as such perhaps the site was dug to provide a healing bath. Perhaps we shall never know, but what is clear is that the site is slowly disappearing into obscurity.

St Bede has a long association with Jarrow but whether he knew of this well is unproved. The legend locally says that when living at St. Paul’s Monastery he would send the monks out to collect water from this well. However, it has been questioned why? Especially as the well is some distance away, a well was found enclosed in the site and in fact the river nearby would have been clean enough to drink. It is possible that the site derives its name from the Anglo-Saxon word baed meaning bathing place and as such perhaps the site was dug to provide a healing bath. Perhaps we shall never know, but what is clear is that the site is slowly disappearing into obscurity.

Folklore

Folklore

The earliest reference to this site is Floyer in 1702 which notes that

“Nothing is more Common in this Country… for the preventing or curing of Rickets, than to send Children of a Year old and upwards, to St Bede’s… Well”

Brand (1789) says that:

“about a mile to the west of Jarrow there is a well, still called Bede’s Well, to which, as late as the year 1740, it was a prevailing custom to bring children troubled with any disease or infirmity; a crooked pin was put in, and the well laved dry between each dipping. My informant has seen twenty children brought together on a Sunday, to be dipped in this well; at which also, on Midsummer-eve, there was a great resort of neighbouring people, with bonfires, musick, &c”.

A report in the Sunderland Times quoted by Hope (1893) notes that:

“Still, when the well is occasionally cleared out, a number of crooked pins (a few years ago a pint) are always found among the mud. These have been thrown into the sacred fount for some purpose or other, either in the general way as charms for luck, or to promote and secure true love, or for the benefit of sick babies… In days when the ague was common in this country, the usual offering… was a bit of rag tied to the branch of an overhanging tree or bush”

A visitor reported an early morning journey to the well, where ‘he seated himself on a rail to enjoy the singing of the birds. Before long an Irishman came up, who had been walking very fast, and was panting for breath. He took a bottle out of his pocket, stooped down and filled it from the well, put it to his mouth, and took a copious draught. “A fine morning, sir”, said our friend. “Sure and it is”, replied the man, “and what a holy man St Bede must have been! You see, when I left Jarrow, I was as blind as a bat with the headache, but as soon as I had taken a drink just now, I was as well as ever I was in my life”. So he filled his bottle once more with the precious liquid, and walked away.