Standing Stone? (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – SE 2428 2329

Archaeology & History

My first hint at the existence of this once valuable archaeological relic came as a result of me seeking out the history and folklore of some hitherto unknown, forgotten holy wells in the Batley and Dewsbury area. I located the material I was looking for on the old wells, but my fortuitous discovery of this site, the Old Wife’s Stone, blew me away!

It was the place-name of ‘Carlinghow’ about one mile northwest of the grid-reference above that initially caught my attention. From an antiquarian or occultist’s viewpoint, it’s intriguing on two counts: the first is the element ‘how‘ in Carlinghow, which can mean a variety of things, but across the Pennines tends to relate to either an ancient tribal or council meeting place, or a prehistoric burial cairn: an element that wasn’t lost in the giant archaeology survey of West Yorkshire by Faull & Moorhouse (1981). But the first part of this place-name, ‘carling‘, was the exciting element to me; for it means ‘old woman,’ ‘old hag,’ ‘witch’ or cailleach! The cailleach (to those who don’t know) was the prima mater: the Great Mother deity of our pre-christian British ancestors. Meaning that Carlinghow hill was a hugely important sacred site no less—right in the heart of industrial West Yorkshire! What is even more intriguing—or perhaps surprising—is that we have no record of such a powerful mythic creature anywhere in local folklore… Or so it first seemed…

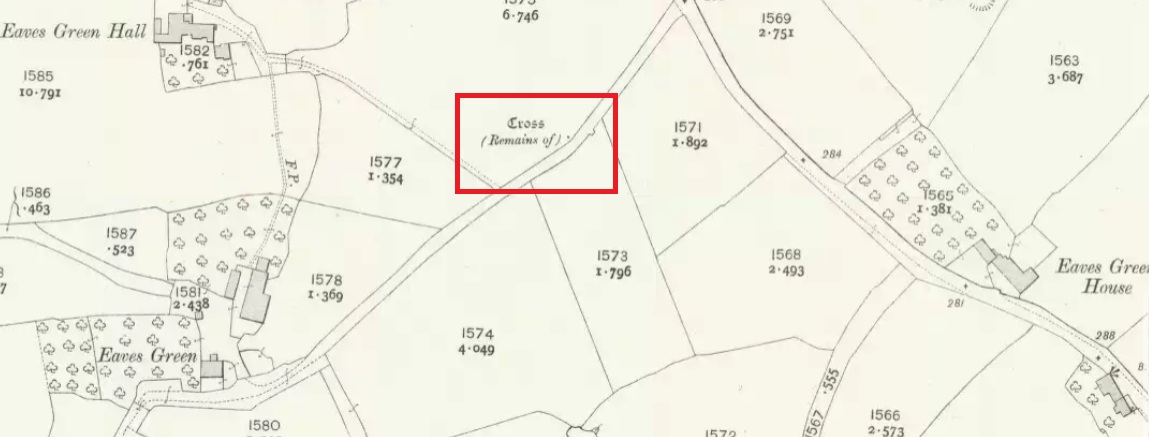

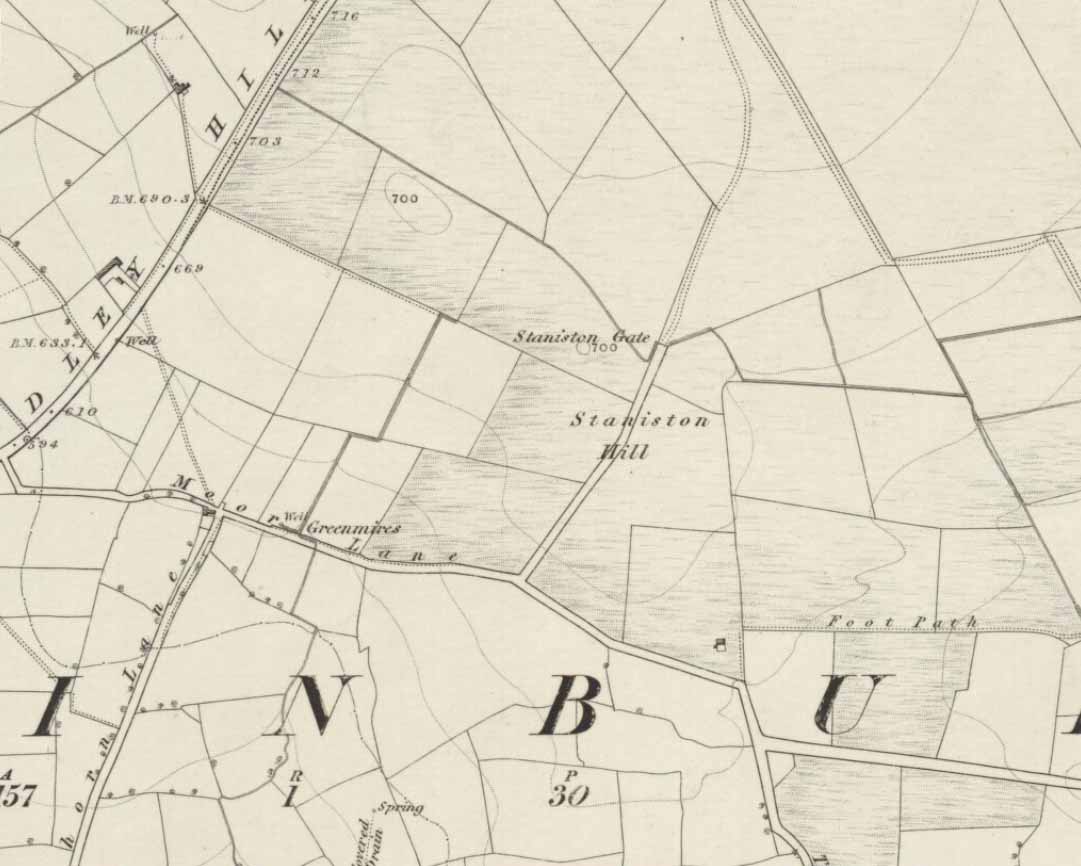

Memory told me that no such prehistoric remains were recorded anywhere in that area—and certainly no prehistoric tombs. I scoured through my library just to triple-check, and found the archaeological records as silent as I first thought. Just to make sure I spent a day at the Central Library, where again I found nothing… So then I explored the region on the modern OS-maps, only to find that much of the area where the Carlinghow place-name existed was, surprisingly, still untouched by housing and similar modern pollutants. This was a great surprise to say the least. And so to check for any potential archaeological sites which might once have been in the Carlinghow area, I turned to the large-scale 1850 OS-maps (6-inch to the mile).

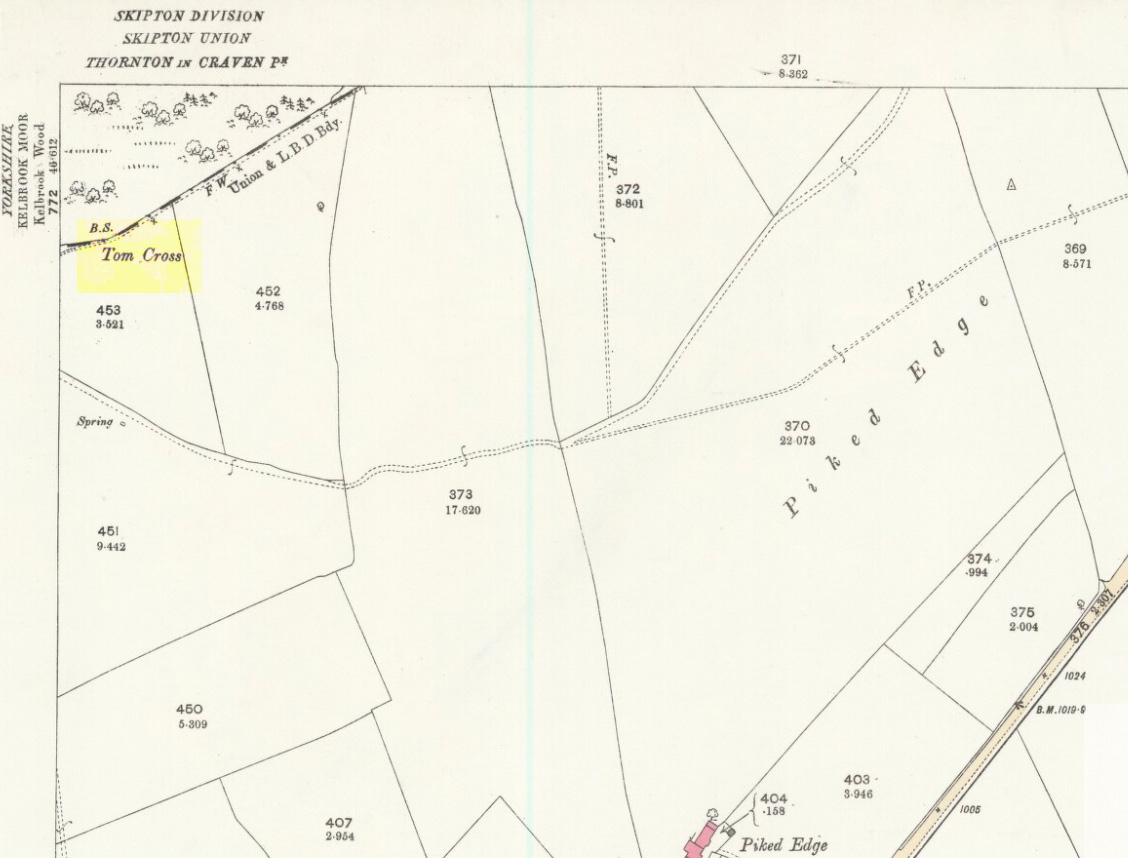

This is when I came across the Old Wife’s Stone, marked in the middle of fields on the outskirts of old Batley. There was no notice of it being a standing stone, or a simple boulder, or archaeological relic—nothing. But its place-name compatriot of ‘Carlinghow’ was the rising hill about a mile to the northwest. In days of olde, if Carlinghow was indeed the ‘burial tomb of the Old Woman’ or ‘meeting place of the cailleach’ (or whatever variants on the theme it may have been), it may have marked the setting sun on the longest day of the year if you had been standing at the Old Wife’s Stone – a midsummer sunset marker no less. (There are other ancient and legendary sites scattering northern England and beyond that are dedicated to the Cailleach, like the Old Woman Stone in Derbyshire, the Old Wife’s Neck in North Yorkshire, the Carlin Stone in Stirlingshire, the Old Woman Stone at Todmorden, Carlin Stone of Loch Elrig and many more.)

As if these curious ingredients weren’t enough to imply something existed in the heathen pantheon of Batley before the Industrialists swept away our indigenous history, we find echoes of the ‘Old Woman’ yet again, immediately east; this time where the animism of water and trees enfolded Her mythos in local rites and traditions, thankfully captured by the pens of several writers, and transmuted into another guise—but undeniably Her! But that, as they say, is for another day and another site profile…

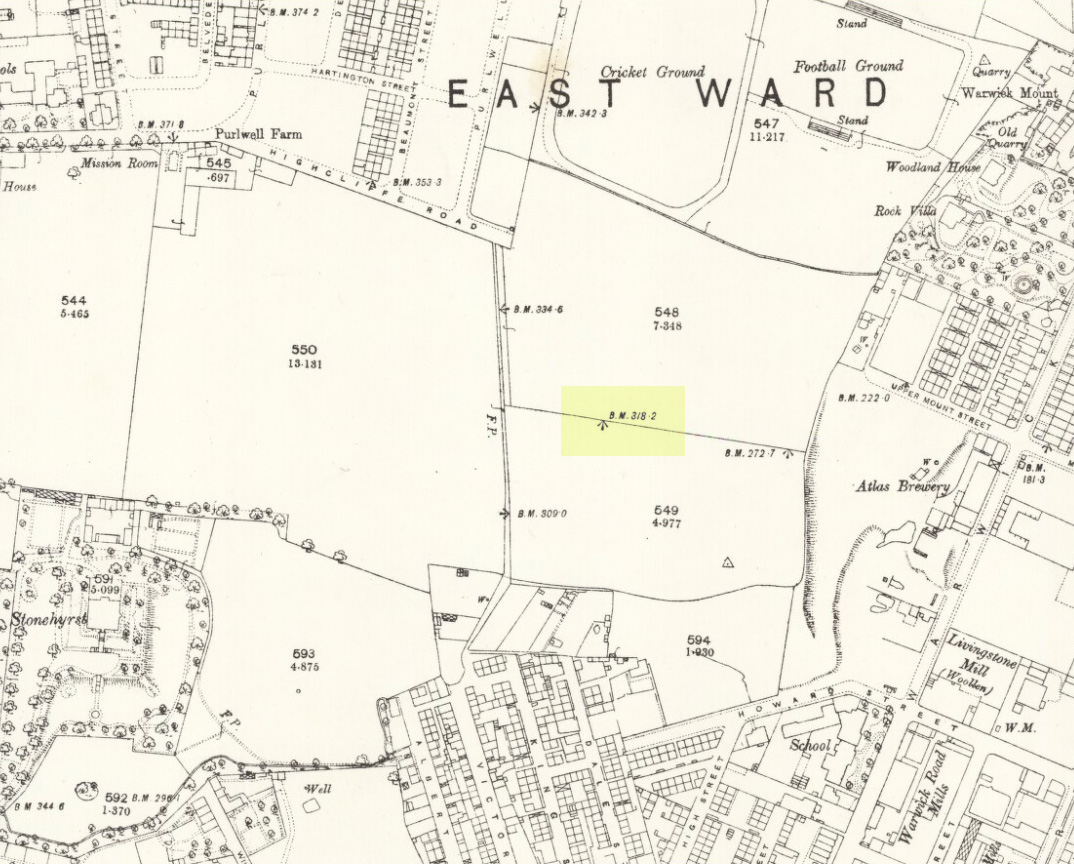

So is our Old Wife’s Stone (or for that matter, Carlinghow’s old tomb) still in evidence? A school has been built where it was highlighted on the 1854 OS-map and, from the accounts of local people, seems to have long since disappeared. The stone looks to have been incorporated into a length of walling, sometime between 1854 and 1888, and a bench-mark of “BM 318.2” carved onto it. But when the Ordnance Survey lads re-surveyed the area in 1905, this had gone. I have been unable to find any more information about this site and hope that, one day, a fellow antiquarian or occult historian might be able to unravel more of its forgotten mythic history.

References:

- Faull, M.L. & Moorhouse, S.A. (eds), West Yorkshire: An Archaeological Survey to 1500 AD – volume 1, WYMCC: Wakefield 1981.

- Goodall, Armitage, Place-Names of South-west Yorkshire, Cambridge University Press 1914.

- Keighley, J.J., ‘The Prehistoric Period’, in Faull & Moorhouse, 1981.

- o’ Crualaoich, Gearoid, The Book of the Cailleach, Cork University Press 2004.

- Smith, A.H., English Place-Name Elements – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1956.

- Smith, A.H., The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire – volume 2, Cambridge University Press 1961.

- Wright, Joseph, English Dialect Dictionary – volume 1, Henry Frowde: London 1898.

Acknowledgements: Many thanks for the assistance of Simon Roadnight and Julia King in the Batley History Group.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.