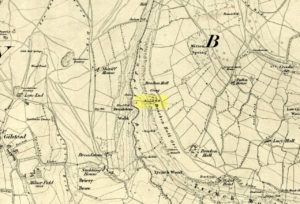

Cross (destroyed): OS Grid Reference – NU 0708 1445

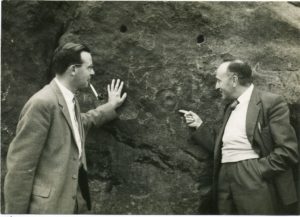

Archaeology & History

This site has long since gone, but its existence is worthy of note. Indeed, when Dippie Dixon (1895) wrote about it in his classic work, faded memory was all he could tell of it too, saying:

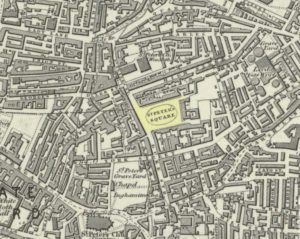

“Glanton once possessed a market cross. Not a vestige of it now remains; but it is said to have stood about the centre of the village, on a slight knoll facing the Whittingham road…”

This would place it close to the old Red Lion pub. Old crosses that are found at the centre of a village or township represent (albeit forgotten) the spot whence the community was born: a faded form of an omphalos, in the christian guide; later debased into little more than where markets and trade was done. When the ‘market’ wasn’t active, it was the gathering place for local people. As George Tyack (1900) told us:

“The village cross, in its more humble way, played the same part in the rustic life of its neighbourhood as did the high cross in the more bustling life of the town. Such public matters as stirred the still waters of rural existence were there discussed: the items of news from the great world without that reached the village gossips were there recounted, and the summons to the yearly Manorial Court, and other notices not suitable for procalmation in church, were there made public.”

This is the mundane function of the cross. In its earlier status, it was the animistic symbol not only of the centre of the village, but the origin of the world itself, where moots or gatherings took place annually, calendrically, to ritually re-establish and commemorate the birth of the local tribe and their world through consecration. But all of this has long since faded…

References:

- Dixon, David D., Whittingham Vale, Robert Redpath: Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1895.

- Eliade, Mircea & Sullivan, Lawrence E., “Center of the World,” in Encyclopedia of Religion – volume 3, MacMillan: New York 1987.

- Tyack, George S., The Cross in Ritual, Architecture and Art, William Andrews: London 1900.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.