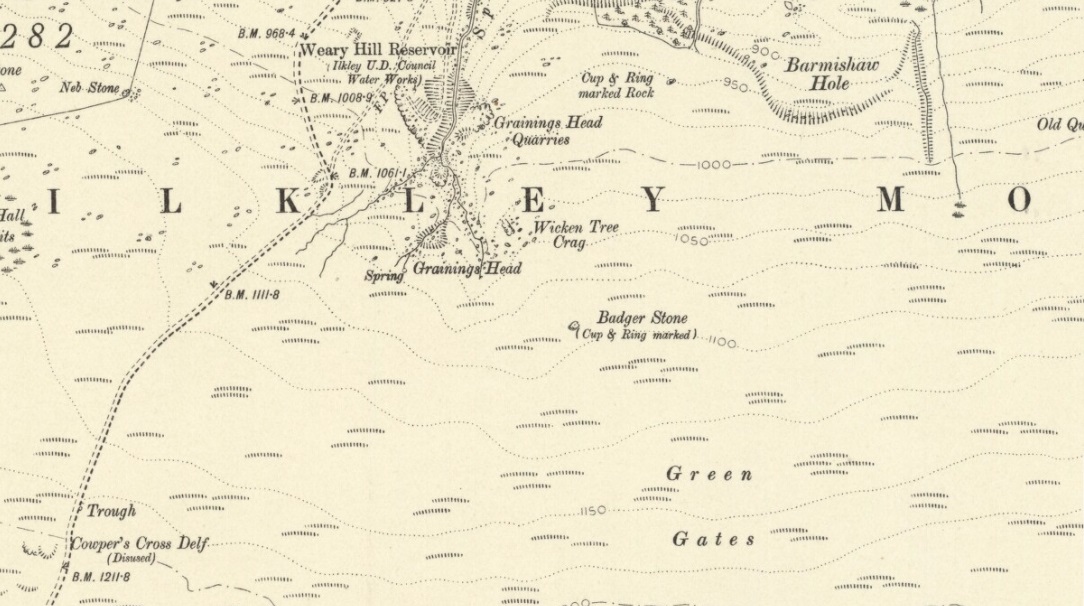

Cup-and-Ring Stone: OS Grid Reference – SE 11074 46049

Also Known as:

- Carving no.88 (Hedges)

- Carving no.250 (Boughey & Vickerman)

- Grainings Head Stone

Although there are several routes to this site, for those who are not used to walking or find maps difficult to read [get a life!], it is best approached from the Ilkley side of the moor. Follow the old track that cuts the moor in half past the remains of Graining Head quarry where the moor begins to level out. Once here cut straight east until you find the footpath which, after a while, you will see leads to a wooden seat right in the middle of nowhere. Here is our Badger Stone.

Archaeology & History

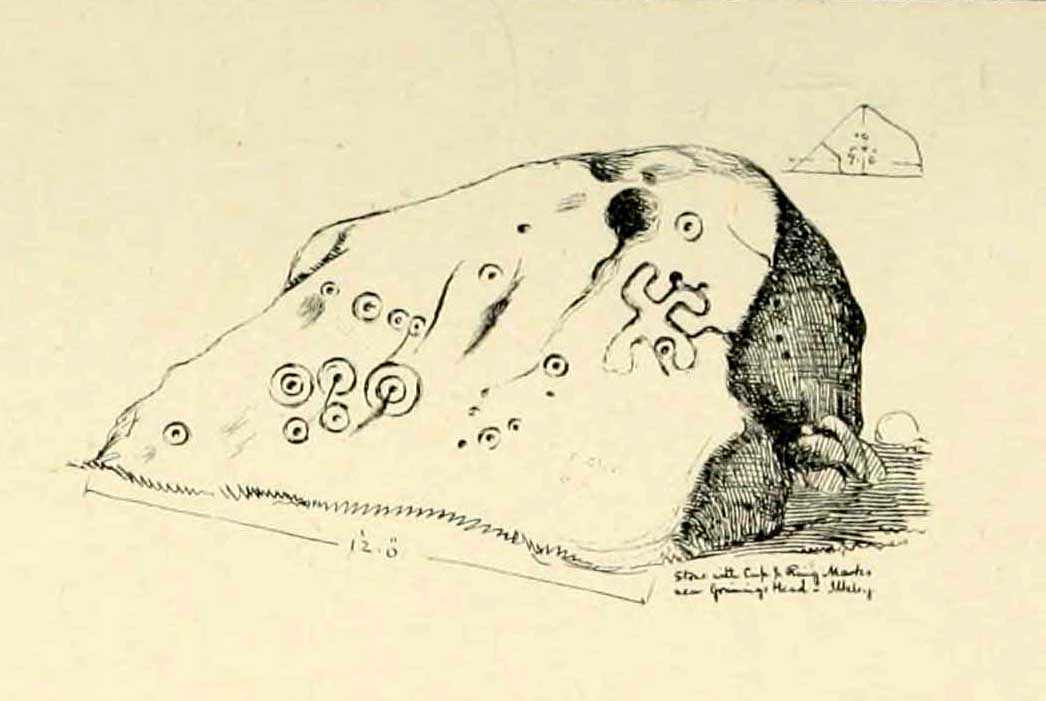

An eroded but quite excellent cup-and-ring stone — one of the very best on Ilkley Moor — comprising nearly a hundred cups, ten rings, what seems to be a half-swastika design, plus a variety of other odd motifs. It’s one of the best carvings on the entire moor and has been written about by many folk over the years. First described in an early essay on cup-and-ring stones by J. Romilly Allen (1879) — who must have visited it in poor light, as some elements of the carving weren’t noticed — he described it as a “sculptured stone near Grainings Head”, saying:

“This stone…is a block of gritstone 12ft long by 7ft 6in broad, by 4ft high. The largest face slopes at an angle of about 40° to the horizon, and on it are carved nearly fifty cups, sixteen of which are surrounded with single concentric rings. At the west end of the stone are a group, three cups with double rings and radial grooves. At the other end, near the top, is a curious pattern formed of double grooves, and somewhat resembling the “swastika” emblem… At the highest part of the stone is a rock basin 8in deep and 9in wide. On the vertical end of the stone are five cut cups, three of which have single rings. This is one of the few instances of cup and ring marks occurring on a vertical face of rock.”

The title “badger” dates back to at least medieval times when, as the Yorkshire historian Arthur Raistrick (1962) explained, the word represented “a corn dealer, corn miller or miller’s man.” It is likely that this traditional title goes much further back, probably into prehistory, as grain was one of the earliest forms of trade. Very close to this sacred old stone are place-names verifying this, like Grainings Head and Green Gates. A little higher upon the moor is the twelfth century Cowper’s Cross (which used to have cup-markings etched upon it) where, tradition tells, a market was held that replaced an older one close by.

Our Badger Stone rests beside the prehistoric track which Eric Cowling termed “Rombald’s Way” (after the legendary giant, Rombald, who lived with his old wife upon these hills): an important prehistoric route running across the mid-Pennines. This ancient route runs east-west, traditionally the time of year when agricultural needs are greatest at the equinoxes. This may have been the time when any ancient grain traders met here. (In modern times a number of archaeologists have emphasized such routes as “trade routes”: a notion that derives from the modern religion of Free Market Economics in tandem with the rise of Industrialism and social Darwinism, much more than the actuality of them as simple pathways or means of accessible movement).

There are accounts from other places in Yorkshire about these badger men. We find a number of other “badger” stones, gates, ways, stoops and crosses on our Yorkshire hills. One of them in North Yorkshire, wrote Raistrick (1962), “is an ancient trade way.” In Richmond, North Yorkshire, around the time of the autumn equinox, Badger men from across the Dales followed the old routes over the hills into town, held annual festivities and sold their grain. (see Smith 1989; Speight 1897) It is perhaps possible that our old Badger Stone would have been a site where some form of indigenous British Demeter was revered.

Some parts of Badger Stone have what could be deemed as primitive human images (anthropomorphic) mainly on the northwestern side of the carving, emerging from the Earth itself. And certainly amidst he same portion we have a very distinct solar symbol, very much like the ones found at Newgrange and, for that matter, many other parts of the world.

Some New Age folk have given the fertility element to the Badger Stone a deeper status, using imagination as an aid to decode these old carvings. When feminist New-Age writer Monica Sjoo visited Badger Stone she described it as “erotic”, with the carvings giving her a distinct impression of “vulvas” and she also thought orgies of sorts had been enacted here. (Billingsley & Sjoo, 1993) The vulva imagery is a well-known idea to explain cup-and-rings and in some cases this will be valid; but when I passed an illustration of this rock-art to a number of people (all women), there was not a vulva to be mentioned — merely the OM symbol, sperm entering the egg, a snail, a bicycle, a willy, a paw-print, eyes, a face, a tadpole, cartoon breasts, the rear end of a dog, grapes, letters, numbers, ears and a snake! Awesome stuff! Take a look at the design yourself and see what you can see in it. Answers on a postcard please! (The dilemma of making specific interpretations of these carvings is that we tend to approach them with dominant ego perspectives, many of them reflecting little more than our own beliefs or search for identity, imposing unresolved journeys and conflicts on that which we encounter, as with the above case.)

As with prehistoric rock-art in general, they are a number of things: functional, ritual, history, spirit; different at each and every site. As if to exemplify this at Badger Stone, note how the detailed carvings have been executed mainly on the southern face of the stone. The northern face has little if anything to show on it. It would suggest therefore, that this stone had some mythic relationship with events during daylight hours. But we have to be careful here…

At sunrise on a good morning, we note how the eastern edges of this stone show up very clearly indeed. If Nature’s conditions are damp and wet (as they tend to be each morning on the hills), the visible outline of these cup-and-rings show up very clearly indeed. Oddly, as the sun then passes through the daytime sky each and every day on its cyclical movement, the petroglyphic content becomes a little less visible unless the stone is wet. Indeed at sun-high (midday period) the carving doesn’t show up as well as it did in the morning light. And we find the same characteristic as the sun goes to set in the west: where that part of the carved stone shows up very clearly again — much clearer than during full daytime hours. If rain has fallen, the glyphs stand out very clearly indeed.

As all cultures imbued the natural world with animistic, living qualities, it seems probable that these periods of the day (sunrise and sunset) were significant at this particular carving. It may be, very simply, that the Badger Stone “came to life” with the sunrise and its mythic nature was alive during this period; whereas with many other carvings (both on these moors and elsewhere in Britain) their strong mythic associations related to the northern Land of the Dead. But then, I could be talking bullshit!

The Badger Stone is also a strong contender for it being a painted stone. Many petroglyphs like this in other cultures were ceremonially coloured-in using lichens and other plants dyes at certain times of the day or year, relating specifically to important mythic relationships between the people and the spirit of the rock at such places. This very probably occurred here.

References:

- Allen, J. Romilly, “The Prehistoric Rock Sculptures of Ilkley,” in Journal of the British Archaeological Association, volume 35, 1879.

- Bennett, Paul, The Old Stones of Elmet, Capall Bann: Milverton 2001.

- Billingsley, John & Sjoo, Monica, “Monica Sjoo in West Yorkshire,” in Northern Earth Mysteries, no.53, 1993.

- Boughey, Keith & Vickerman, E.A., Prehistoric Rock Art of the West Riding, WYAS: Leeds 2003.

- Hedges, John, The Carved Rocks on Rombald’s Moor, WYMCC: Wakefield 1986.

- Cowling, Eric T., Rombald’s Way, William Walker: Otley 1946.

- Raistrick, Arthur, Green Tracks on the Pennines, Dalesman: Clapham 1962.

- Smith, Julia, Fairs, Feasts and Frolics: Customs and Traditions in Yorkshire, Smith Settle: Otley 1989.

- Speight, Harry, Romantic Richmondshire, Elliot Stock: London 1897.

© Paul Bennett, The Northern Antiquarian

The map could not be loaded. Please contact the site owner.

Reblogged this on erkembode and commented:

a brilliant blog post about the Badger Stone, Ilkley Moor…

Reblogged this on Stuart France.